Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

Hortense describes what it’s like when the big lie faction comes in and take over. We see here the techniques that were used to isolate Napoleon and leave him bereft of all support. The ones who weren’t quick to just sell Napoleon out now get their special personal come ons to do so. Their efforts particularly focused on separating Hortense from Napoleon. These divide and conquer tactics are played in such a sneaky manner that the target doesn’t fully understand what was done to them until it’s too late and they are trapped into what is basically a diabolical pact.

We study this book to learn these tactics so that these tricks will no longer work on us. Can you see that these same tactics have been consistently targeted at me? You know them by their actions.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

CHAPTER XII

THE FIRST RESTORATION: THE DEATH OF JOSEPHINE (APRIL 16-MAY 31, 1814)

The Return to Malmaison--A Visit from Emperor Alexander—The Treaty of April 11, 1814—Napoleon at Elba—Josephine and Madame de Remusat—Eugene in Paris—Business Affairs—An Excursion to Marly—The Etiquette at Saint-Leu—A Newspaper Article—Josephine's Last Illness and Death—The Farewell of the Emperor of Russia—The Inheritance of the Empress.

AT one o'clock in the afternoon [April 16, 1814] I arrived at Malmaison. I was astonished to find the courtyard crowded with Cossacks and I inquired the reason for their presence. I was told it was because the Emperor of Russia was walking about the garden with my mother.

I went to look for them and met them near the hothouse. My mother was delighted and surprised by my arrival. She kissed me tenderly and said to her companion: "This is my daughter and these are my grand-children. You must take good care of them." She released the arm of the Emperor, who immediately offered it to me.

Thus, we found ourselves, the Emperor Alexander and I, side by side, without having looked at one another or exchanged a word. We were some little distance from the rest of the company and rather embarrassed in beginning our conversation.

My position was a difficult one. Although I had for a long while been hearing favorable comments on my present companion even from Emperor Napoleon himself, and though I had formerly been most anxious to make his acquaintance, this was hardly the moment to say so. A distinctly reserved attitude was what I felt I must adopt toward the man who had invaded and conquered my country. Had he not begun to talk about the visit I had just made the Empress Marie Louise, I believe I should not have managed to say a word.

Fortunately, this awkward situation did not last long. We arrived at the chateau where my mother and children joined us. With her usual grace my mother found subjects to talk about. The Emperor, in phrases which seemed sincere, deplored the ravages of war and assured us that far from seeking to satisfy any personal ambition his sole purpose was to put an end to the slaughter.

These sentiments at least consoled me more or less for the sad position in which France was placed. I was grateful to him for expressing them, but I remained silent.

He petted my children a great deal and asked me "What is there I can do for them? Please let me look after their interests.” I replied that although I appreciated his offer there was nothing I needed for my children.

He left, and my mother reproved me for the distant manner with which I had treated him. I pointed out to her how misplaced any display of warmth would have been toward a man who had just declared himself the open enemy of the Emperor, whose action had just destroyed my children's future and the position of the family whose name I bore.

I did not dare ask the French nation to share my regrets for the past. People seemed overjoyed at the downfall of the Empire. Every day brought letters and resolutions from all parts of the kingdom approving what had taken place in Paris, and thousands of voices saluted the Restoration as ushering in a new era of freedom.

The less the changes of fortune affected me personally, the less I considered myself justified in betraying my absence of concern at what had taken place. The public would not have understood my point of view. In its hastily formulated judgments, it would have considered me hypocritical, as I should presumably have been afflicted by this change in my social position, and my misfortunes would indeed have justified my being sad. It would have required only a slight effort on my part to adopt the proper attitude and it was my duty not to lower myself in the eyes of the public.

I also felt uncomfortable to hear the Emperor so frequently accused of being responsible for having postponed a peace that everyone desired so eagerly. The foreigners were all the time talking about establishing that era of good will which was so necessary for the human race, and lavishing on France all sorts of magnificent promises of riches and happiness of all kinds.

I was jealous at seeing them act in this manner. I did not at the time realize that all their promises were merely snares and delusions, and that the unhappy masses were soon to find themselves worse off than they had been before. I shall not go into the details of the Emperor's abdication.

I shall not examine the motives of those who advised it. I prefer to speak only of those who behaved well up to the very end. Among them Marshal Macdonald and the Due de Vicence deserve especial mention. The Duke deserves credit for the way in which he defended the interests of the Emperor and his family. He wrote me a letter about what he had done on my behalf in the treaty of Fontainebleau, where it was decided that I could continue to be separated from my husband and where the guardianship of my children was assured me, a clause for which he had secured the approval of Emperor Napoleon. This is what he wrote:

Madam, Your Majesty retains her children; she may continue to live among her friends. Everything she cares about has received as favorable treatment as circumstances will permit. I am pleased at having been able to secure conditions which will be agreeable to her and of which I wish to be the first to advise her. Your Majesty is aware how devoted our family is to her. I hope she will count on this devotion and that in the midst of the misfortunes which surround her she will continue to rely on our respect and loyalty.

I remain, etc. CAULAINCOURT, DUC DE VICENCE. Paris, April 11, 1814

He sent me at the same time the clause in the treaty which referred to me and which read as follows:

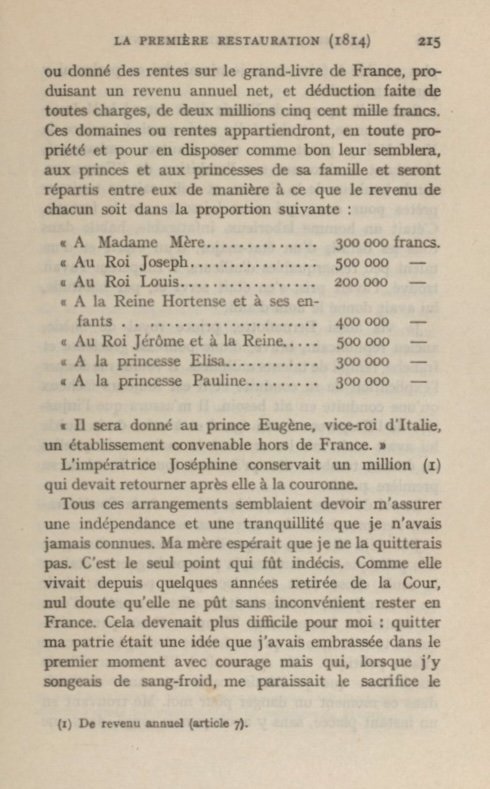

ARTICLE VI. In the countries whose sovereignty the Emperor relinquishes for him and his family, certain estates, or sums taken from the Treasury, furnishing an annual income, free of all charges, amounting to two million five hundred thousand francs, shall be set aside. These estates or funds to belong to and be the property of the princes and princesses of that family to do with as they see fit. They shall be divided among them in such a manner that the income shall be apportioned as follows:

To Madame Mere [Napoleon's Mother] . 300,000 francs

To King Joseph . 300,000

To King Louis . 200,000

To Queen Hortense and her Children . 400,000

To King Jerome and the Queen. 500,000

To Princess Elisa . 300,000

To Princess Pauline . 300,000

There shall be set aside for Prince Eugene, Viceroy of Italy, a suitable domain outside of France.

The Empress Josephine was to keep an income of a million francs, which reverted to the State after her death. All these agreements made it appear as though I were about to enjoy an ease and independence such as I had never known before.

My mother hoped I would remain with her. This was the only point that had not yet been settled. As she had for the last few years been living in seclusion and not appearing at court, there could be no harm in her staying on in France. This was more difficult for me. The idea of exile had been one which at first, I was ready to accept but which, when I reconsidered it, seemed like too much of a sacrifice. I did not dare to speak of it to her nor think of it myself.

As the Emperor of Russia had paid us a visit at Malmaison everyone felt the need of following his example. The Prince of Neuchatel was among those who called.

He appeared embarrassed and sought to find excuses for his conduct, speaking of the Emperor's ambitions, the happiness of France, and a thousand other phrases which always occur to those who desert us in hope of making their fortune elsewhere.

He was an industrious soul, hard-working, skillful in the performance of his duties as a staff officer, but possessing neither a remarkable mind nor much cleverness.

The Emperor had found him, taken him, used him, and from force of habit come to consider him as a friend. I also saw Bernadotte, the Swedish Crown Prince. He had formerly been a republican, was honest, possessed a gracious and polite manner and remarkable military talents.

He wished to explain his conduct, and it is always awkward when your conduct requires explanation. He assured me the Emperor's unfair attitude toward him and toward Sweden was the only reason for his taking up arms against his former master, and that these arms had been unused since he set foot on his native soil.

The King of Prussia and the Princes of the Confederated German States also hastened to call on my mother. I have already said that until then I had remained entirely ignorant of political matters in general. The result attained, peace or war, being the only thing, which gave me cause for joy or grief. This was in fact true of all women during the Empire.

Everyone would have thought it ridiculous for a woman to have anything to do with political matters. The Emperor had set the fashion in this respect. In view of the prominent position I occupied, this ignorance became dangerous for me at the time to which I now refer. I found myself suddenly in a position such as I never imagined I should be called to occupy ; the whole question of our national interests and rights, the sentiments people might try to make me and my family express, the role they sought to make us play were all equally unfamiliar to me.

One day the Empress brought in to me Marshal de Wrede, whom the King of Bavaria had sent to see her in regard to her son's position. "Now," she said, "I shall leave you with my daughter. She knows better than I do what would be best for her brother." A few months before the Allies entered Paris, the King of Bavaria had written my mother, seeking to win Eugene away from the imperial cause.

The original French is available below: