Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

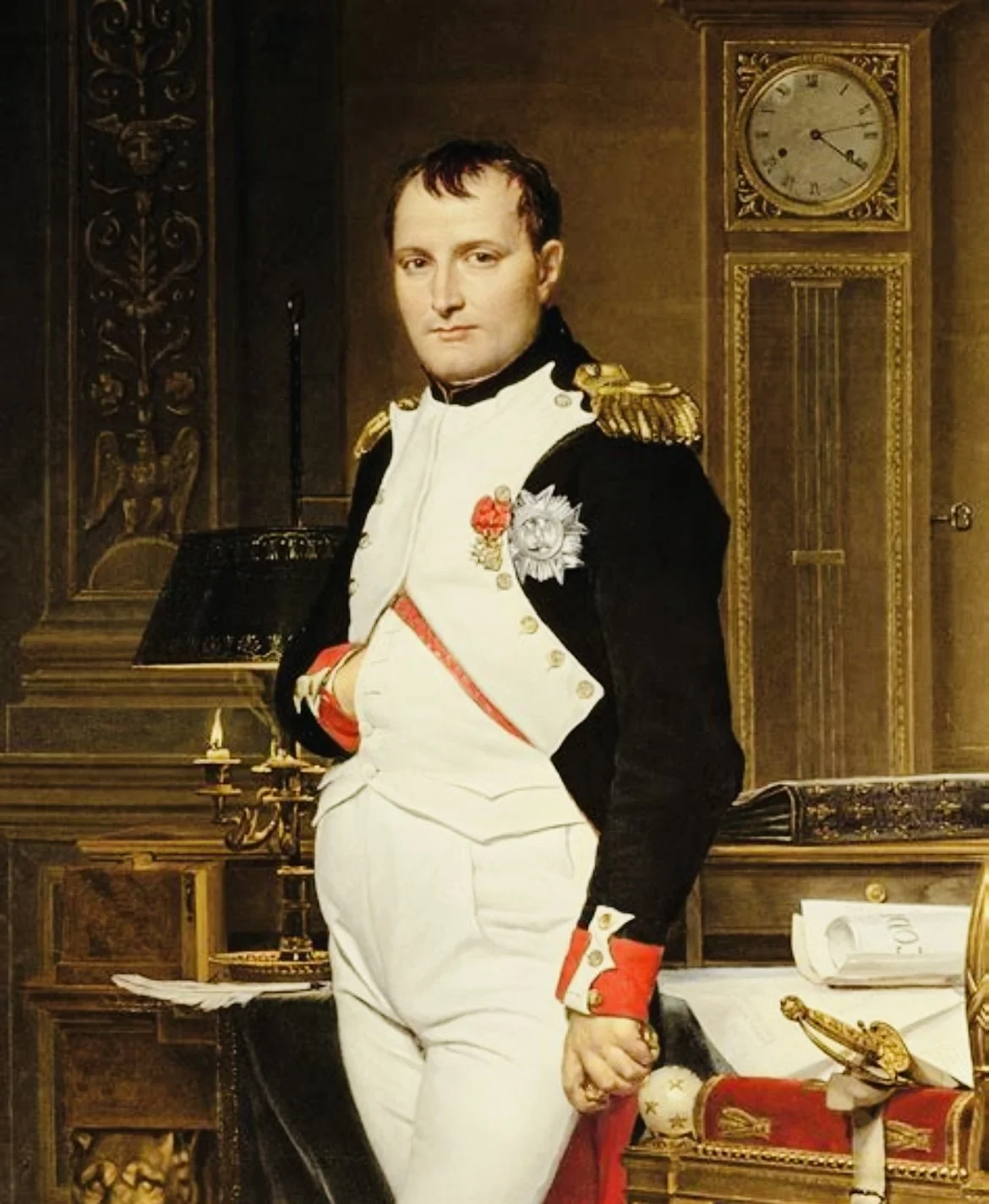

Throughout this book, Hortense blames Napoleon for inciting Caroline against her because he showed Hortense too marked a preference. That Napoleon thought it was a good idea to have Hortense and Caroline as rivals in performing dance spectacles shows that his skill at dealing with women really wasn’t that great. Caroline was always dangerous to Napoleon and he should’ve handled her better.

Hortense seems to imply that a hidden hand was involved in even these silly pageants.

This excerpt also contains the passage where Napoleon complains about little boys wearing epaulettes and how they have to earn them first but he likes that there’s a trend in that direction.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

Caroline, who lived at the Tuileries, heard the news first, and instead of talking the matter over with me at once drew up a list of the handsomest women and most popular men and sent out invitations to them to appear in her performance. I was at home in the evening with my ladies in waiting, the officers belonging to my household, and a few young men whom I knew when the grand marshal of the palace appeared with the Emperor's invitation, which the Queen of Naples was supposed to have sent me the day before.

I feared the task of rehearsing and carrying out a pageant would greatly tire me. I wished to decline, but everyone protested against my doing so. People pointed out that it was not the Queen of Naples who should do the honors of the Court of France. I should not submit to having my place taken like that and risk at the same time angering the Emperor.

Moreover, my friends considered that dancing instead of tiring me would do me good, and they promised to take all the other trouble off my shoulders. Especially they agreed to prevent my being obliged to talk much, as that would tire me, and to carry out my orders without discussion. I allowed myself to be convinced and accepted the offers of the young men who happened to be present.

Among them were Messieurs de Sainte-Aulaire, Germain, de Flahaut, de Canouville and several others. They all asked to be included in my ballet and suggested that I send word immediately to other persons I wished to include, being convinced, so they said, that the latter would prefer to be with me rather than with the Queen of Naples.

I therefore sent out my chamberlain, who arrived at the same time as the Queen's cards of invitation. The written invitations were all refused, the verbal ones accepted.

The Queen was greatly vexed and complained to the Emperor, who paid no attention to her. The court was large enough to allow both pageants to be composed of pretty women, but mine included the better dancers, and the absence of these made a difference in the general effect. The Queen of Naples together with Princess Pauline had decided to present an allegory representing the reunion of Rome and France. She had selected the day of the costume ball. Much to my satisfaction I had been given that of the masked ball, which was to take place several days later.

The rivalry which sprang up between the performers in the two pageants was really amusing. The men, even the least frivolous, took the matter seriously. People called with sincere regret to inform me that the other pageant contained many clever and witty allusions in praise of the Emperor of France, and so on. I was urged not to be in any way inferior and to choose some allegorical subject also. I needed all the eloquence of my feeble voice to say repeatedly that we were not asked to dance in order to pay compliments to the Emperor. I knew he would not care for them and I believed personally that society people never danced well enough to undertake to execute pas seuls, which should be performed only by professional artists who are sure of their skill.

Moreover, an allegory acted out by people whom one recognizes may easily seem silly, whereas the attractiveness of a society pageant lies entirely in the beauty and richness of the costumes displayed, the way in which the colors harmonize, the good taste shown in the dances performed and the perfection of the whole spectacle.

Another time people came and begged me to allow them to add more ornaments to the costumes. Each of them was willing to sacrifice the general effect for his private convenience, but as it was I who gave the costumes I insisted that my wishes be carried out. I sometimes felt like laughing when I saw the grief and disappointment caused by my decisions, especially when certain inquisitive people had succeeded in discovering all the marvelous features which were to be included in the rival pageant. On the day the ball was to take place the theater of the Tuileries was transformed into a ballroom.

The Emperor was seated on a raised platform between the Empress and me. All the court and important foreign visitors filled the hail itself, and the boxes were given to the Parisians. The beauty and the jewelry of the two princesses were dazzling. One of them represented Rome, the other France. Their charming faces, their little helmets, their shields covered with diamonds and colored stones sparkled gaily.

The other women, dressed as water nymphs of the Tiber, the Hours, Iris, were all handsome and graceful, but the faces of the equerries and chamberlains, which one recognized as impersonating Stars, Zephyrs and Apollos, aroused mirth.

The pantomime did not seem appropriate either to the dignity of the persons acting in it or to the place where it was being performed. After the performance of the masque the Empress and I opened the ball with a French square dance.

Later other dances followed. The Emperor meanwhile went about speaking to everybody. He did not say a word about the pageant, but the next evening when I arrived to call on him and the Queen of Naples was also present, he said in a rather impatient tone:

“Where did you get the idea for your ballet? It was all nonsense. Rome has submitted to France, but it is not happy about it. Whoever gave you the idea of showing her as pleased and satisfied at being a dependent state? It was a ridiculous piece of flattery. I know of course that you only wished to look pretty and wear a handsome costume, but you could find other subjects and not try and set politics to music."

Then turning to me he added: "How about you? Are you too going to give us some sort of silly show? I warn you I don't like compliments." I hastened to say that my masque had nothing to do either with politics or with him.

“All the better," he said. Then, because he saw how marked a superiority he was just then giving me over to his sister, who after all had only been trying to please him, or perhaps because he felt like finding fault and recalled subjects that lent themselves to his humor, he continued as he walked up and down the drawing-room, “Ah, these young women. They are harder to keep in order than a regiment. After all I don't bite people's heads off. One can speak to me, consult me about what one is going to do. Not a bit of it. These ladies act as they choose. Yet in the position we occupy everything we do is important."

Then speaking directly to me he went on: "You, for example, what were you thinking of when you dressed up your son as a Polish lancer? Do you know I came near having war on your account? Do you know that Kourakin has complained about it, and the rumor has got about that I intend to make your son King of Poland? And what right has he to wear the epaulette of a captain? One must have fought to obtain that. You knew I made him take off his Dutch decorations because I do not wish any child belonging to the imperial family of France to wear a medal he has not earned. My family must do as I did and win everything at the point of the sword. If after all," he added more gently, "in order to have your son look well he must have a uniform, well, then dress him as a Red Lancer of the Dutch Guard. I will even go so far as to let him wear a second lieutenant's epaulette, which I hope he will later earn himself."

I had made no attempt to reply as long as the Emperor was speaking, for it was my mother who had made the Polish uniform as a New Year's present. The tailor had put on an epaulette and, as a matter of fact, I had never noticed it nor had anyone else.

The original French is available below: