Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

This excerpt is very special because it recounts how Hortense met Napoleon, the man to which she became utterly devoted to an extreme degree. It turns out that she didn’t like him at first and was revolted at the idea of him becoming her stepfather.

…

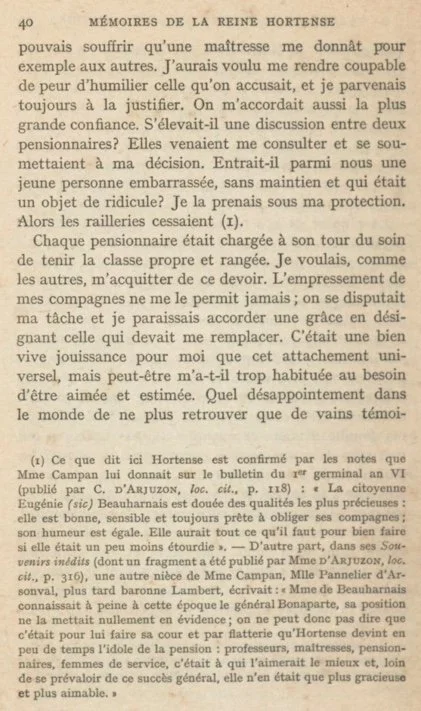

If a new girl entered the school who was awkward in her behavior and was made fun of by the other pupils, I would take her under my protection and at once the teasing would stop. Each girl was supposed to take her turn in keeping the classroom neat and tidy. I was anxious to do my share, but whenever my turn came the other girls struggled to be allowed to do my work for me. It was considered a privilege.

This general admiration was very dear to me, but perhaps it caused me to become too accustomed to being sincerely liked and admired. What a disappointment it is when we realize that the people about us are generally hypocrites. This is especially true if your nature is too sensitive not to be hurt by that casual attitude which criticizes without taking the trouble to understand, or that malicious spirit which condemns unjustly. I can declare, however, that the fact of being admittedly a favorite at school aroused in me only an overmastering desire to deserve this popularity. Later this wish to be liked did me harm, for having acted as I thought for the best, I could not understand why I did not receive the praise I felt was due me. My mother had put us in school but she could not bear not to see us often and very frequently we were sent to Paris.

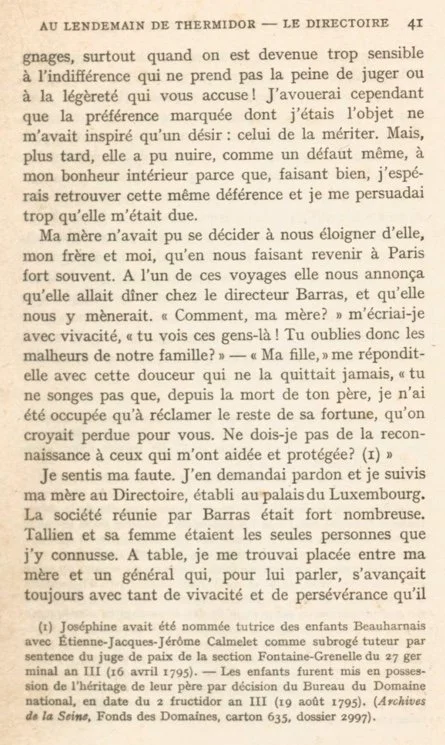

During one of these trips she informed us she was dining with the Director Barras, and that we were to accompany her. "Is it possible, mother," I exclaimed impetuously, "you actually associate with such people? Have you forgotten our family misfortunes?"

“My daughter," she answered with that angelic gentleness which never left her, "you must consider the fact that since your father's death I have been obliged to attempt to save as much of his fortune as possible in order that it should not be lost to you. Should I be ungrateful toward those who have helped and protected me?"

I recognized that I was wrong. I begged my mother's pardon and went with her to the Directory established in the Palace of the Luxembourg. Barras had invited a number of guests, of whom Tallien and his wife were the only ones I knew. At the dinner table I found myself placed between my mother and a general who, in order to talk to her, kept leaning forward so often and with so much vivacity that he tired me and I was forced to push back my chair.

I thus found myself obliged to examine closely his countenance, which was handsome, very expressive, but remarkably pale. He spoke with great animation and apparently devoted his entire attention to my mother. It was General Bonaparte, and his interest in her was due to an incident which I must relate.

Following the riots, in the 13th Vendemiaire [October 4, 1795] a law was passed forbidding any private citizen to have weapons in his house. My brother, unable to bear the thought of surrendering the sword that had belonged to his father, hurried off to see General Bonaparte, who at that time was in command of the troops stationed in Paris.

He told the General he would kill himself rather than give up the sword. The General, touched by his emotion, granted his request and at the same time asked the name of his mother, saying he would be glad to meet a woman who could inspire her son with such ideals.

Whatever might have been the cause, the General's very evident interest in my mother reminded me that she might someday remarry. This idea was painful to me.

As I told my brother with whom I discussed the matter, "She won't love us as much as she does now."

When the General called at our house, he felt the coolness of our reception. He did his best to change our attitude, but his method with me did not succeed. He tried to tease me, making fun of women in general, and the more vigorously I defended my sex the more violently he attacked it.

I was about to be confirmed. The General declared I was bigoted. When I answered, "You were confirmed. Why shouldn't I be?" he laughed at having roused my temper. I, not guessing he was doing this only in jest, replied seriously to all his remarks and took a dislike to him. Every time I came to Paris from Saint Germain, I found him more assiduous in his attentions to my mother. He had become the center of her little group of friends, which included Madame de Lameth, Madame d'AiguilIon, Madame de la Galissonniere, Madame Tallien and several men.

The General's conversation was always worth listening to. He even managed to make the ghost stories he occasionally told interesting by the way in which he related them. Indeed, he was so openly admired by the little group that I could not refrain from informing my mother of my fears. She only combated them half-heartedly. I wept as I begged her not to remarry, or at least not to choose a man whose rank would separate her from us.

But already the General's will had more weight than mine. I know however that my grief caused my mother to hesitate for some time. She did not yield until she saw the General about to leave without her. He had been appointed commander-in-chief of the army in Italy. She loved him and could not bear the thought of giving him up. Finally, she consented to become his wife. It was Madame Campan who broke the news.

Eugene de Beauharnais when he was Général Bonaparte’s aide de camp.

Our mother, aware of the sorrow it would cause me, did not dare to do so herself. As a matter of fact, I felt very badly about it. Madame Campan attempted to quiet me, pointing out how this marriage would help my brother's career. He looked forward to being a soldier and could not be one under better auspices than those of a general who was also his stepfather. Moreover, the General had not been implicated in the horrors of the Revolution.

Contempt for the laws, and the disturbance of public order, are the results of weakness and wavering in princes.