Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

Good cop bad cop is a game where the target is expected to cling to the “good cop” to beg for protection from the “bad cop”. Follow this part of the story and see if you can trace out that pattern in how Hortense was being handled. It is also interesting that Hortense was discouraged in her desire to contact the current - installed by foreigners - King of France and also Napoleon. It is typical of abuse to keep the victim from access to communication in this manner.

In this passage, we see more rampant media deception in order to isolate Hortense and leave her bereft of support. This is an elaborate campaign that was ultimately successful in pretty much destroying her life and her potential for happiness.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

He described how the Emperor of Austria had heard of my mother's death. In the morning as he was going out alone, he met a common workman in the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. This man, not knowing who he was, stopped him and said: "Have you heard the news? That kind woman the Empress Josephine is dead."

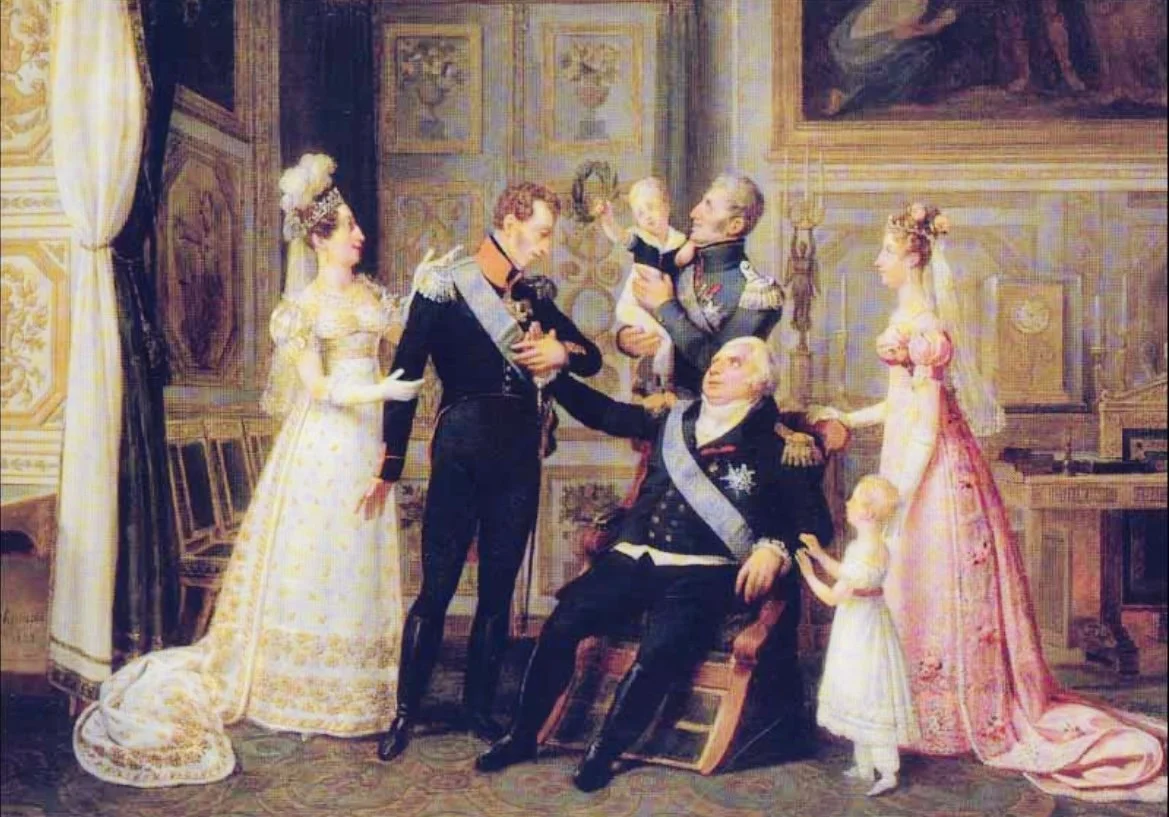

This is an example of how widespread the grief was. Emperor Alexander received several messengers during the day he spent with us. He wrote dispatches and walked about with my brother. I dressed and came downstairs, and we all had dinner in my little drawing room. He should have left that same evening, but I heard since, he wished to be sure before going that the question of the letters patent creating the Duchy of Saint-Leu had been satisfactorily arranged.

The King had strongly objected to signing them on account of their referring to me under the title of Queen. The Emperor of Russia had been obliged to declare that his troops would remain quartered in Paris until those letters had been sent off.

He received them in the course of the evening, but did not wish to hand them over to me himself. He felt that they had lost much of their value to me, since they were intended to assure that I should remain with my mother, and she now was no more.

He sent for my reader and told her that when it would be possible to discuss business with me she was to tell me I need not make any acknowledgment or express my thanks in any way to the King of France, as he [the Emperor of Russia] was exceedingly annoyed at the reluctance which had been shown in arranging the matter, and that I must not expose myself to a possible rebuff.

The Duc de Vicence came in, in the evening, and informed us that the King had at last signed the treaty of April 11, but that this was due to the vigorous intervention of the Emperor of Russia.

The Duke had at once, with the permission of the government, dispatched one of the Emperor Napoleon's servants to convey this news to him at Elba. The Emperor of Russia spent that night also at Saint-Leu and left very early the following morning for England after telling Eugene he would see him at the Vienna Congress.

My brother and I both wished to write to the Emperor Napoleon to inform him of our recent loss, but the messenger of the Duc de Vicence had already left, and we could not secure permission to send another.

I was most anxious also to let him know how my personal affairs had been arranged, but the Duc de Vicence told me he had already done this, and that after having described the negotiations to the Emperor he had added, "As for Queen Hortense, suitable provisions for her and her children are being arranged in France."

His letters were sent by a servant who was going to Elba with them. It was therefore impossible to write direct, as all correspondence with the Emperor had been forbidden. Therefore, we considered it best to wait till matters had become calmer. In the first few days that followed our bereavement all Paris society came to see me.

So much sympathy with us was liable to offend the government. We already knew that it was distinctly hostile toward us. My brother felt the drawbacks of a prolonged stay in France and he wished to conclude his affairs and leave afterwards for Munich. Monsieur Soulange and Monsieur Devaux were appointed to settle my mother's estate, which people said was a very considerable one.

Yet it consisted only of her country place at Malmaison, the Château of Navarre, which the Emperor had entailed for my brother, her pictures and diamonds, an income of thirty thousand francs in government securities, and her property in Martinique. But as she never understood much about money matters and as she never knew how to say no to anyone who asked her for something, she left about three million francs worth of debts.

Our business advisors suggested a sale, which they declared would be profitable since everyone was anxious to secure some object that had belonged to her. But it was disagreeable to us to think of all our mother's personal belongings being exposed to the public and knocked down to the highest bidder.

My brother and I therefore agreed that these personal belongings should be given to the young ladies who had been her attendants and whose welfare she looked after. Doubtless in benefiting them we were carrying out her intentions. The income was divided among them to act as dowries when they married. One of them did so at once.

The servants were so numerous that in order to dismiss them and give them six months' wages we were obliged to borrow two hundred thousand francs. Of all the children my mother had undertaken to educate and care for, we took over only those who were in the greatest distress.

The servants who had been with her for several years received pensions, which we promised to continue. My share of these pensions, not including those I was already paying personally in spite of the change in my position, amounted to more than thirty thousand francs annually.

My mother's maids of honor and her equerry each received a carriage and four horses. Her ladies in waiting received shawls and different souvenirs. We were the last to keep anything for ourselves. It seemed as though our position was assured.

I was to receive an income of four hundred thousand francs, and my brother important domains. Our only thought had been to make other people happy; but, do what we could, was it possible to satisfy everybody?

People were discontented. My mother had been in the habit of giving out annually pensions amounting to between two and three hundred thousand francs. We kept only sixty thousand francs of these pensions. It was said that people were being treated unfairly. Servants who were only entitled to fifteen hundred francs allowance a year demanded three thousand.

My brother, because he believed that what the Allies would give him would enable them to pay off the debts of my mother and also because I could do nothing for him, took the real estate. I had only half the picture gallery and half the diamonds.

The newspapers talked of this estate as amounting to fifteen millions. We did not consider it worthwhile to deny these reports, especially as the prominent position my mother had occupied for such a long time made such exaggerated figures seem possible.

It was true she had been wealthy, but she gave away everything she had and frequently more besides. People enjoyed enlarging upon the extent of her fortune as well as ours, in order to contrast the luxury that existed at the imperial court at its most dazzling moment with the so-called distress in which the former royal family were supposed to have lived during their exile.

The Duchesse d’Angoulême went everywhere without any jewelry, wearing no diamonds or cashmere shawl, and seemed very much attached to her little English bonnet. Perhaps this calculated simplicity of appearance was to some people a sign of her former misfortunes, and therefore increased their attachment to her, but others considered it a sign of an entirely foreign education and perhaps of that ignorance of these princes regarding the customs and habits of the country they had been called upon to rule.

The original French is available below: