Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

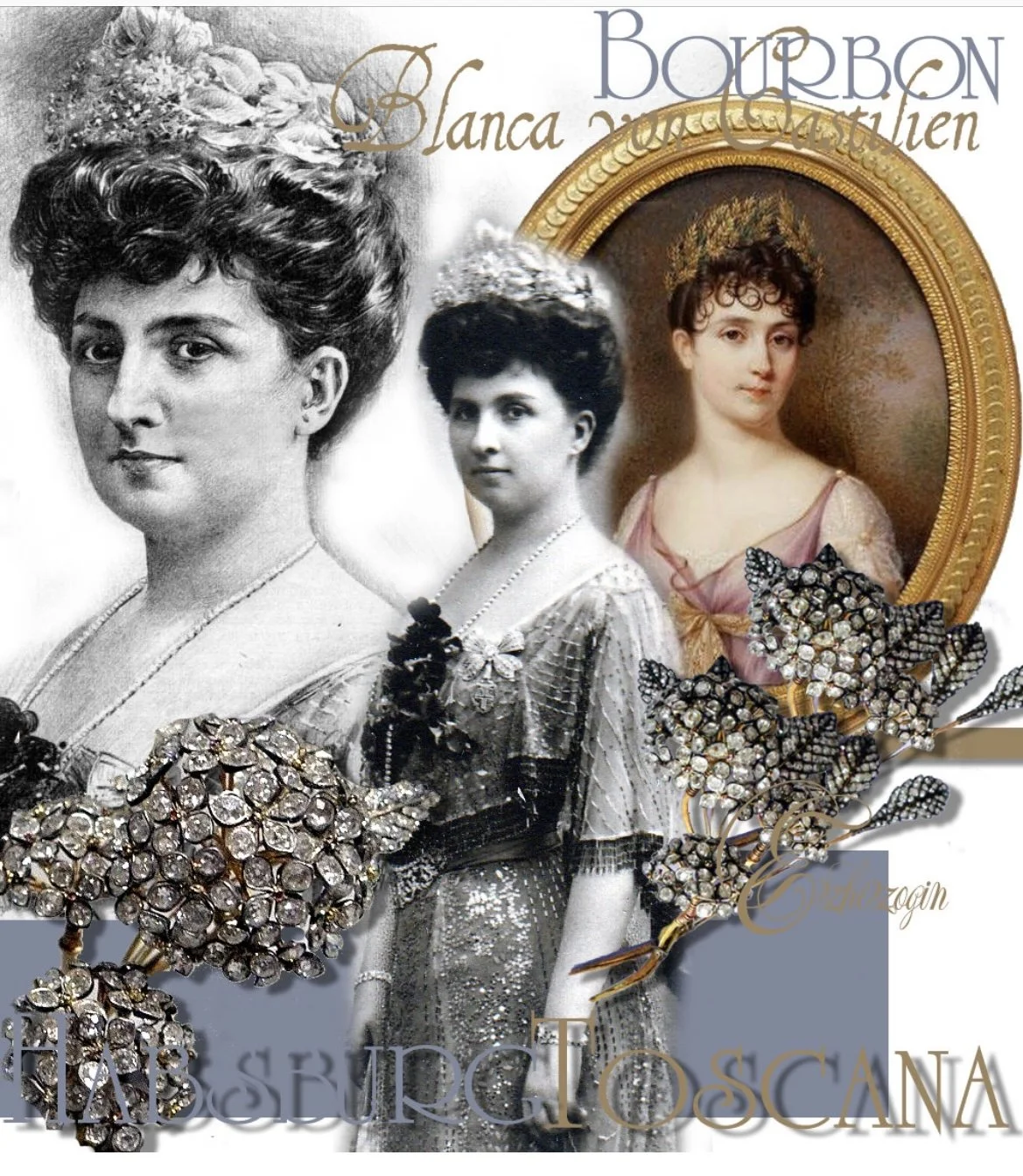

If you look into the history of the most extravagant jewelry, the name Hortense comes up a lot. Napoleon was a lavish giver of sumptuous jewelry to the many women in his life, perhaps to obscure significant gifts he made to the real object of his affection. In this passage, Hortense describes how when Napoleon was disguised, he told Hortense something very revealing about his feelings towards her and his thoughts regarding jewelry.

Napoleon’s last treasure on St. Helena was a “collar of diamonds” that Hortense pressed Napoleon to take back from her. Las Cases was wearing this necklace (to hide it) while Napoleon transmitted history to him and this necklace was given to the one at St. Helena who had pleased him best - his valet Marchand.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

I returned home well pleased, nevertheless, at having insisted on keeping my pageant the way I wanted it, because I saw that my ideas on the matter were the same as the Emperor's.

The costumes I had chosen were dazzling ones. Twenty-four ladies represented the priestesses of the Sun they were all dressed in gold. Twelve ladies and twelve gentlemen were Peruvians, with gold cloth and red plumes covered with diamonds and rubies. I as high priestess was all in silver, white plumes and white diamonds.

Eight ladies also in silver and with white plumes and diamonds and turquoise ornaments surrounded me. All the performers wore little black masks and executed their dances in front of the Sun, which was carried by the priestesses.

Gardel had directed this pageant, which was so much admired that even court etiquette could not prevent violent expressions of enthusiasm on the part of the spectators.

At supper the Emperor said to the Queen of Naples, "Ah, that was better, much better than yours."

As I was masked, I received after our performance quantities of compliments which the fact that I was disguised permitted people to make me. There was no raised platform or throne. Everybody in the room was on the same level, and all wore masks.

A domino whom I recognized spoke to me and said, "How dazzling you are! One cannot look at you."

“I should make a good prize, should not I, with all the diamonds I have on?"

“You know very well," he replied, "that the most beautiful diamond of all, the diamond that is simply priceless, is the one hidden under all the rest."

The domino was the Emperor, and compliments from him were so rare that these remarks flattered me greatly.

The Queen of Naples and the Princess Pauline never forgave me for having scored so evident a triumph even in a matter of such slight importance.

The Emperor liked masked balls. He attended one or two a year, either at the house of the Lord Chancellor or at that of the Prince de Neuchatel. It might have seemed difficult to discover what pleasure he found there, for he never spoke a word.

I, however, could understand him, for I too liked them and I was not any more communicative than he was. To be able to watch people without being noticed or followed is a novel sensation for people who are always being stared at. When you are constantly surrounded with ceremony it is sometimes a pleasure to lose yourself in a crowd.

As soon as he arrived at one of the balls, he sent for me or the Queen of Naples because he thought he would be less readily recognized if he were with a woman. We would walk about without speaking. Sometimes he would ask me, “Who is that person?" I had no idea and I would try to find out.

“How are you, handsome masquerader?" or "What is your name?" were the only phrases I could think of, and my mental effort stopped there. If people guessed who we were they would step aside with a deep bow.

If not, they would turn their backs on us, exclaiming, "How silly they are!" This would amuse the Emperor as much as it did me. After an hour or two of strolling about and looking for the Empress, who was doing the same thing with the Duchesse de Montebello, we would go to supper with the Emperor, the Empress, and the prominent people who happened to be present.

Each one would relate the exploits he had performed in the ballroom. The only amusement the Emperor had had was that of not being recognized, or at least believing he was not recognized, and when people said he was delightful at a ball, that everybody wondered who he could be, this was doubtless a form of humor.

At one of these balls when I was not with the Emperor I happened to sit down to rest on a bench. I caught sight of Monsieur de Flahaut as he passed but did not venture to speak to him although I wanted to do so, for I fancied that everyone knew who I was. A young and very distinguished-looking man came and sat beside me. He seemed rather unhappy. I had seen him once or twice at my formal balls, but he had scarcely heard my voice. I spoke to him in a bantering manner.

During our talk he asked me about all the people who went by and was surprised to find that I knew so many of them. I aroused his curiosity. He did not want to leave and overwhelmed me with questions:

“What do you do all day? Are you married? Have you brothers, or sisters, or children?" Each of his questions made me withdraw into myself. In the midst of this frivolous scene, which had momentarily distracted my thoughts from my troubles, these questions recalled the realities of life. Pain accompanied such reminders and took my mind far from the gay merrymaking which surrounded me and which for an instant had assuaged my distress.

Especially when I heard the phrase, "How many children have you?" the loss of my son came so vividly to my mind that I could not conceal my grief. Forgetting that I was masked I was embarrassed at succumbing so easily to my feelings in the presence of a stranger. For I was unable completely to conceal my emotions and I regretted the fact. To disclose the secrets of your heart, no matter how innocent they may be, as was the case in the present instance, is to reveal too much; it robs friendship of something to which it alone is entitled.

I hastened to escape from the sympathy of this young man and his assiduities. I made him give me his word he would not try to discover my identity and I left with my companions. I do not know whether he kept his promise, but very shortly afterwards at a ball I saw him looking at me earnestly.

Later he wrote me a passionate letter, telling me that he had been in Holland and heard General Bruno speak about me. My sorrows had made a deep impression on him. In looking at the places where I had lived, he came to have only one wish, to meet someday the woman who people told him had been so unhappy, whom he loved without having seen and to whose service he wished henceforward to devote the rest of his life.

I was so much upset by this letter that I decided to ask Monsieur de Flahaut's advice. He told me that men were presumptuous, that they rarely believe in a woman's virtue, that one must be on one's guard against them and especially must never reply to their letters. I followed his advice, but I was worried at the idea that this young man could have misjudged my character since he dared to talk about love to me.

Moreover, since it is generally considered that persons of higher rank are always the first to make advances I felt that I was almost to blame because I had been the first to speak, this in spite of the fact that our talk had been quite a simple one and his letter had received no answer.

Soon I learned he was unhappy; my silence had only further inflamed his passion instead of, as I had hoped, calming it. He even dared to call on my ladies in waiting and appeared to be quite desperate. I was deeply troubled and my only thought was how I could cure him.

Since this method had succeeded with others, one day I asked him to call and said: "Sir, my high rank may have made an impression on your imagination, but you cannot be in love with someone you do not know. Not only do I repulse your advances, I do not believe you are sincere. If you imagined that I might be attracted toward you because I spoke to you at the masked ball, you are mistaken. It all happened by chance. I cannot laugh at sorrow, but I cannot admit exaggerated sentimentality. Prove to me that I deserve your esteem by ceasing to think about me. I promise you to respect you under those conditions." With that I turned away. When I repeated this conversation to Monsieur de Flahaut he said "You believe that this is the way to make people cease to care for you? The better they know you the more they will love you."

“At least they will have respect for me," I answered. "That is all I require. You may be sure that if women without any coquetry, without that air of meaning the opposite of what they say—should act as I do, they would have more friends and there would be fewer of those love affairs that end in bitter quarrels."

I was again right in this case, for the young man afterwards told me that I had done him a great service in speaking to him frankly, and later he proved to me his sincere devotion.

The original French is available below: