Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

Hortense describes what it’s like when a nation regains sovereignty; What it’s like when a nation actually chooses their own leadership. This is an environment where everyone does not need to be bribed, blackmailed, seduced and threatened into suiting the best interests of a small hidden frequently criminal coterie.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

On the morning of March 20, I caught sight of the youthful members of the King's body-guard, who had looked so fiery a short time before, looking downcast as they bade sad farewells to the members of their grief-stricken family. The painter who lived across the street appeared at his window with very preoccupied air.

The huge white ribbon [white being the color of the Bourbons] with which he adorned his buttonhole had disappeared. Armed with a feather-duster he was busy removing the dust from a life-size portrait of one of the Emperor's ministers.

I thought I recognized the likeness as that of Monsieur de Montalivet. The painter's wife, thin and nervous, appeared to be arguing with him vigorously, in a state of great excitement. All these changes made me feel that still others had occurred elsewhere in the capital.

I was impatient to hear the news when Monsieur Devaux arrived and told me that the King had left hastily during the night upon hearing that Marshal Ney and his army corps had gone over to the Emperor.

Monsieur Devaux had heard of this departure from one of the men who cleaned the floors of his house this man was the uncle of a dancer at the Opera [named Virginie], the mistress of the Duc de Berry. During the night of March 19, the prince had come to say good-by because the young dancer had just had a child.

He told her in the presence of her family, whom he urged to take good care of her, "We must separate forever. We have lost everything, no hope remains." I wished to return home immediately, but Monsieur Devaux pointed out that hordes of people without any clearly defined means of livelihood were pouring into Paris, and might the more easily commit excesses of all kinds since the Bourbons had left the capital without any commander or anyone in authority to keep order.

Does it seem possible? In spite of the various emotions which had preyed upon me during the last few days I still was sentimental enough to care about what became of this family who were thus, after a brief return home, once more driven into exile. They must be suffering all those painful sensations which I had a short time before experienced myself, and this idea caused me to feel a sincere sympathy for them.

The Orleans family were those for whom I felt the most sorry. Without knowing any of them personally, their affable behavior, their highly respectable domestic life had charmed those who had come in contact with them, and the sentiment had communicated itself to me.

I recalled that the Duke had received my brother kindly, and in this critical moment when it was possible that the masses might commit some act of violence against them I who had nothing to fear from the mob, would have been glad to be useful to them if the opportunity had presented itself. A few days before, prompted by this feeling, I had sent word to one of my maids, who had been also employed by Mademoiselle d'Orleans [the sister of Louis-Philippe], placing my services at their disposal.

Should they feel that either they themselves or any of their children were in danger I urged them to trust me implicitly. My maid Madame Charles went to deliver my message and came back saying she had not ventured to do so. "Alas," she added, "how could I utter your name when Mademoiselle d'Orleans on catching sight of me exclaimed, 'We are obliged to leave again and it is that Duchesse de Saint-Leu who has caused our ruin'?"

In a moment that was such a critical one for the King, I remembered only the friendly manner in which he had received me, and I thought that at a time when everyone was deserting him it would be agreeable to him to hear I still recalled his kindness toward me.

I wrote him and repeated the expression of my thanks, giving the letter to Monsieur de Lascours, an officer of his body-guard who was to join him abroad. Monsieur Devaux came back at three o'clock and said that in all probability the Emperor would enter Paris that same day.

He had with him a letter which the Duc d'Otrante wished me to forward to the Emperor, it being important, so he said, that the Emperor receive it before entering the city. I believe it was to warn the Emperor to be on his guard against the Chouans in disguise who were planning to assassinate him.

My valet de chambre Rousseau left at once with it. Nothing surprised me so much on my way home as to see along the boulevards how all the shopkeepers were busy changing or turning around their signs. The eagles and the bees were taking the place of the lilies and fortunately this change was the only indication of the great events that had taken place. Perhaps the most amazing, miraculous and unheard-of thing of all was the Emperor's march from Cannes to Paris.

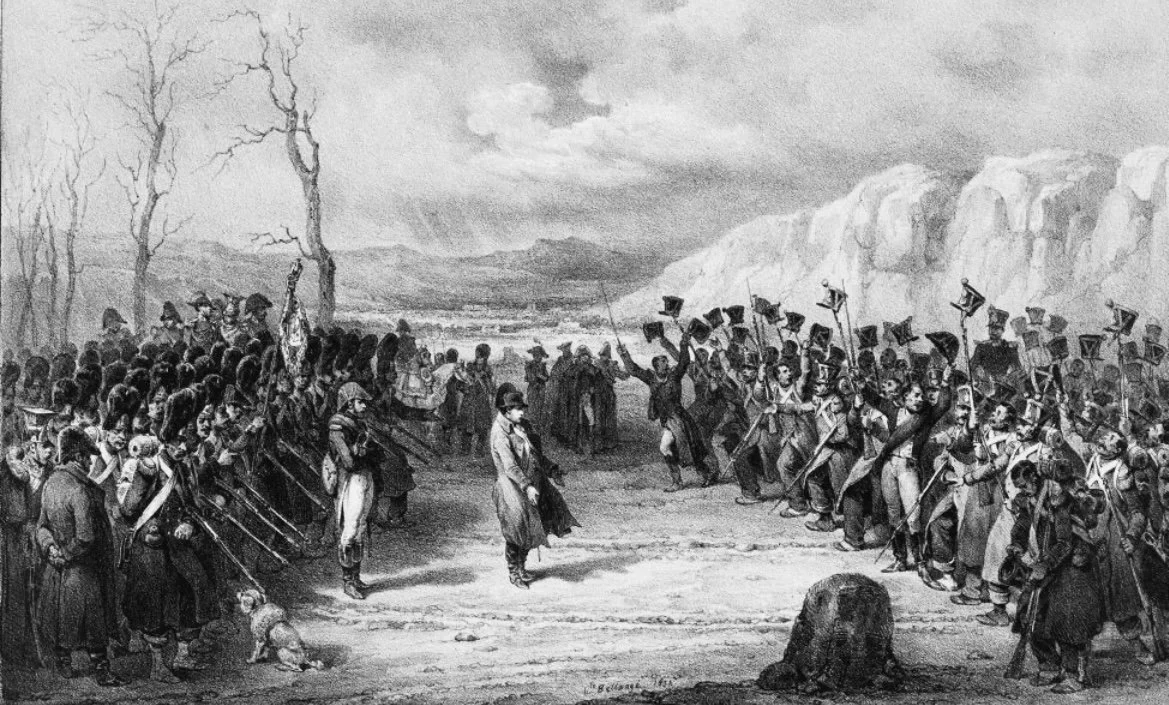

When he came up to the outpost of the first regiment which had been dispatched from Grenoble to attack him the Emperor dismounted, stepped forward alone and said to the nearest soldier, "Do you recognize me? Would you dare fire at your general?"

Cries of "Long live the Emperor!" were the reply and this body of troops joined his force. A short time later Colonel de La Bedoyère brought over his regiment and opened the gates of Grenoble.

From then on as far as Paris the Emperor traveled in a little carriage almost without any escort. As soon as he caught sight of a regiment marching toward him, he would quietly get out, walk forward to meet it, and review it as he had done in the past.

This confidence in the troops conquered them immediately. At first they were astonished; then they became enthusiastic and gave way to their emotion until it seemed to him and to other observers that he had never ceased to be the Emperor of the French.

My valet de chambre met the Emperor near Essonnes, just as he was changing horses, and found the escort so small that he could not realize that this was he.

Having delivered the letter he returned to report that so many country folk were hurrying up from all sides to see the Emperor pass and so many Parisians were going out to meet him that he had been obliged to come back at a snail's pace.

Everywhere the enthusiasm was intense. The troops who had concentrated at the camp at Melun and who had taken their places along the Essonnes road shouted, "Long live the Emperor!" as soon as they caught sight of him, and certain generals who till then had been rather undecided allowed themselves to be carried away by the impetus of the crowd in spite of the opinions they had held the day before.

They have since declared, "The princes were not there what could we do?" The Emperor's former aides-de-camp as well as the Duc de Vicence had left the morning of March 20 to meet him and had joined him at Essonnes.

He embraced them all and had the Duc de Vicence step into his carriage where there already were General Drouot and General Bertrand. An officer of the National Guard came at seven o'clock in the evening to invite me to go to the Tuileries to await the arrival of the Emperor.

The officer was sent by the former cabinet ministers. Crowds surrounded the palace. The sight of my carriage caused much cheering. The sentries belonging to the National Guard were turned out and they saluted as I arrived.

They cheered so loudly that I thought it must be the Emperor who was approaching. When I discovered that the demonstration was in my honor I could not help smiling, for I remembered that a few days before I had passed this same spot quite unrecognized by the men on duty.

How quickly things change! I found many officers and ladies assembled in the apartments of the former cabinet ministers. Among the ladies were the Duchesse de Bassano, Duchesse de Frioul, Duchesse Duchesse de Rovigo, Madame Gazzani and Madame Lallemand.

Queen Julie [wife of Napoleon's brother Joseph, King of Spain], who happened to be in Paris seeking to regain possession of her estate of Mortefontaine, which had been sequestrated, arrived a moment after I did.

The renewed cheering that greeted her made us again imagine it was the Emperor. Night had fallen. The crowd withdrew. People did not believe he would arrive till the next day. Had he postponed his entry till then his reception would have been a real triumph, but he never on any occasion made a formal state entry into Paris.

He always returned to his palace after dark. It was not till the next morning that his arrival was announced. Perhaps in this particular instance he wished to return on March 20th, the anniversary of his son's birth.

The original French is available below: