Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

Hortense reaches a point where she realizes that sharing the company of her abuser will not help her or him. She’s going to have to “appear cruel and selfish” to strangers who don’t care about her in order save herself and her children. Enabling abuse is not nice in any way and yet victims are so often pressured to feel they must continue to keep giving abusers the upper hand - or else they are labeled as bad and wrong in some way. The spiritual reality behind our earthly existence is revealed within this eternal dynamic. Predation is happening at a spiritual level and we need to become aware of that. Our vigilance and the maintenance of our safety and boundaries is the antidote.

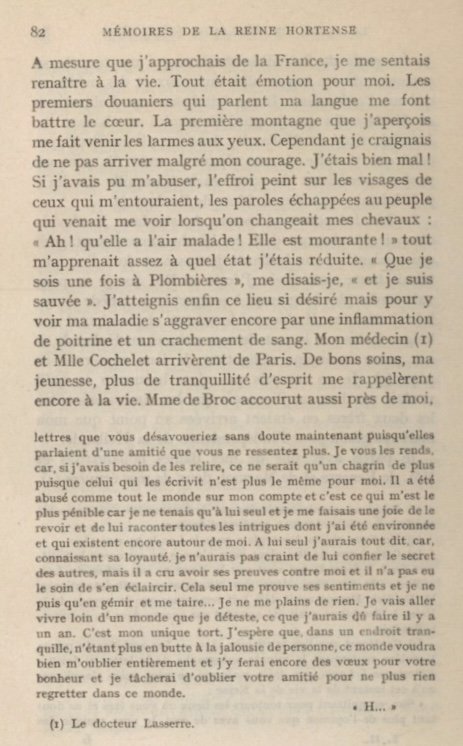

The following letter from Hortense to Louis shows how fed up she was with her situation. For clarity, I’ll post the original French and the English translation below the text from the French edition of Hortense’s Memoirs.

Note that Hortense mentons in this letter the constant hidden hand machinations that follow her wherever she goes. Hortense was a targeted individual. My experience is the same as hers at this point.

This ABUSE needs to end. We need to ward off this international spy system with its leadership in Europe. Please help me ward off this group! I don’t deserve to be hounded, harassed and intimidated because I am trying to educate people about our rich history and our collective truth.

Sire, en quittant pour toujours les lieux où vous êtes et ne doutant plus de l'opinion que vous avez de moi, je vous renvoie des lettres que vous désavoueriez sans doute maintenant puisqu'elles parlaient d'une amitié que vous ne ressentez plus. Je vous les rends, car, si j'avais besoin de les relire, ce ne serait qu'un chagrin de plus puisque celui qui les écrivit n'est plus le mème pour moi. Il a été abusé comme tout le monde sur mon compte et c'est ce qui m'est le plus pénible car je ne tenais qu'à lui seul et je me faisais une joie de le revoir et de lui raconter toutes les intrigues dont j'ai été environnée et qui existent encore autour de moi. A lui seul j'aurais tout dit, car, connaissant sa loyauté, je n'aurais pas craint de lui confer le secret des autres, mais il a cru avoir ses preuves contre moi et il n'a pas eu le soin de s'en éclaircir. Cela seul me prouve ses sentiments et je ne

puis qu'en gémir et me taire... Je ne me plains de rien. Je vais aller vivre loin d'un monde que je déteste, ce que j'aurais dû faire il y a un an. C'est mon unique tort. J'espère que, dans un endroit tranquille, n'étant plus en butte à la jalousie de personne, ce monde voudra

bien m'oublier entièrement et j'y ferai encore des vœux pour votre bonheur et je tâcherai d'oublier votre amitié pour ne plus rien regretter dans ce monde.

Hortense.

…

Sire, leaving forever the places where you are and not doubting any more the opinion which you have of me, I send back your letters which you would undoubtedly disavow now since they spoke of a friendship which you no longer feel. I am returning them to you, because, if I needed to read them again, it would only be one more heartbreak since the one who wrote them is no longer the same to me.

He was abused like everyone else on my account and this is what is most painful to me because it was up to him alone to vindicate me and I would have been happy to see him again and to tell him of all the intrigues of which I have been surrounded and which still exist around me.

To him alone I would have said everything, because, knowing his loyalty, I would not have feared to confer on him the secrecy of the others, but he believed to have his proofs against me and he did not take care of himself enough to clarify the truth. That alone proves his feelings towards me and there’s no use in moaning and being silent ... I'm not complaining about anything. I'm going to move away from a world I hate, which is what I should have done a year ago. It is my only fault. I hope that, in a quiet place, no longer the butt of anyone’s jealousy, this world will want well to forget me entirely and I will still make wishes there for your happiness and I will try to forget your friendship so as not to regret anything in this world.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

I felt that unless I had the courage to ask permission to go away I should in a short time not have enough strength to go. The terror with which my husband inspired me was still so acute that I hardly dared ask him a question.

I finally ventured to do so. I told him that the air of Amsterdam was killing me and reminded him of his promise to allow me to go and take the waters whenever the doctors prescribed scribed them for me.

He made many objections, but it was finally decided that I might go to the Chateau of Loo in Holland, where the air would be better than what I was breathing at the time.

The idea of leaving my son behind pained me, but I felt reassured as to his health since I left Madame de Boubers to take care of him. Loo was for me like Amsterdam. I felt that my only salvation was in those happy hills where my bright youth had been spent and whose air was what I so dearly desired.

I wrote the King that I could no longer put off trying this cure which had in the past proved so beneficial. He did not dare to refuse me, but replied by a long letter in which he spoke of the future of my children in Holland and of our duty to keep this country for them to reign over.

I did not at that time understand very much what he was writing about, for I was unaware of the fact that the discussions between the two brothers had reached a point where my husband was afraid that Holland would lose her independence.

I left with two of my Dutch ladies in waiting and two of my equerries, Monsieur de Renesse and Monsieur de Marmol. As I drew nearer France, I felt that I was being restored to life. Everything stirred my emotions. The first custom-house officials we encountered made my heart beat faster because they spoke my language.

The first hill I caught sight of made tears come to my eyes. Yet I feared I should not be strong enough to reach my goal. I felt so weak. If I had been inclined to have any illusions about my appearance the alarm of those about me, the words uttered involuntarily by the people that came to catch a glimpse of me while our horses were being changed would have made me realize what a condition I was in.

“Ah, how ill she looks! She must be dying."

“If only I can reach Plombieres," I said to myself, "I shall be saved." Finally, I arrived but only to see my illness become more acute due to an inflammation of the chest and an expectoration of blood.

My own doctor and Mademoiselle Cochelet came from Paris. Careful nursing, my youth, a greater peace of mind were what restored me to life.

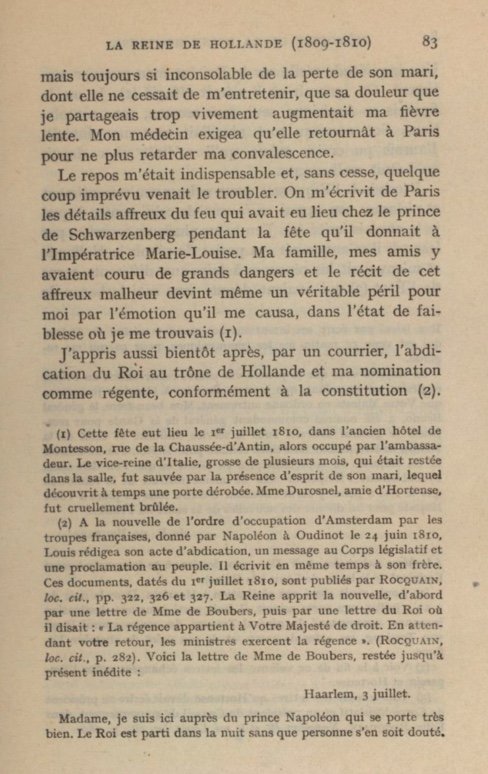

Madame de Broc hastened to me. She was still inconsolable for the loss of her husband, about whom she kept talking to me, and her grief, which I shared so intimately, increased my fever. My doctor insisted that she return to Paris in order not to hamper my convalescence.

It was absolutely necessary that I should rest. Yet constantly something came up that prevented my being quiet. From Paris I received letters giving horrible details regarding the fire that had taken place during a reception given for the Empress Marie Louise by the Prince of Schwarzenberg.

My family, my friends had been in danger, and the account of this terrible accident became a real danger in itself for me, so keen was the emotion it aroused in my enfeebled condition. Immediately afterwards a messenger brought me word that the King had abdicated the throne of Holland and I had been named Regent in accordance with the constitution.

Real anxiety as regards what had happened to the King was my first reaction. No one knew where he had retired.

I imagined that he had left for America, alone, with no one to help him, no one to console him. His fate aroused my sympathy. I almost came to believe that I had become fond of him, now that he had known misfortune.

I wrote the Emperor, seeking to calm his resentment against my husband and asking him to help the latter even though he might be angry with him. I received several messages to the effect that he intended to annex Holland and telling me what I should reply to the various legislative bodies whose delegate the Baron von Spaen came to inform me of my appointment as Regent.

The Emperor's letters contained severe reproaches in regard to my husband's conduct. Frequently a single word summed up an incident, and his irritation showed itself in the violence of his expressions. For instance, he said, "The King went away leaving his son utterly destitute."

I should have understood that the phrase was dictated by his irritation, but it touched me at my most sensitive point. The tense state of my nerves, the strain resulting from the continual arrival of messengers combined to inspire me with the most gloomy thoughts.

I was haunted by the idea that my son was alone, without anyone to care for him. I forgot the throne which he still occupied and thought only of his complete isolation and my inability to help him.

The moment I received news of what was happening I sent Monsieur de Marmol to bring the child to me. But the Emperor had acted first. One of his aides-de-camp, Monsieur de Lauriston, brought the boy to Saint Cloud after he had reigned for a week, having already received the oaths of allegiance from the various branches of the government before the union of Holland and France was announced.

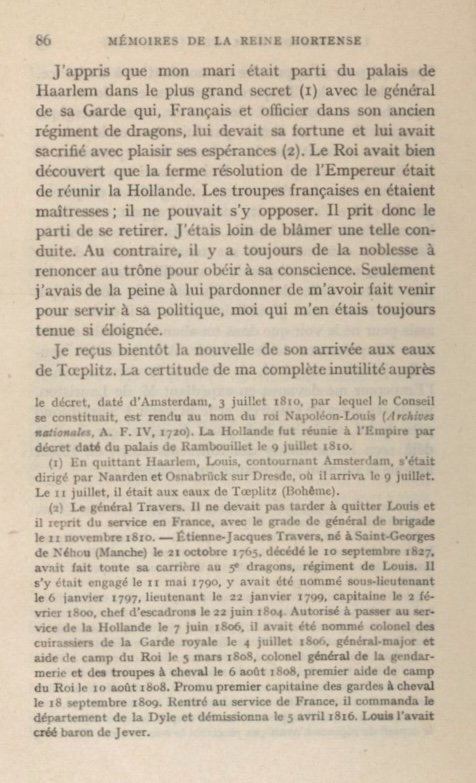

I heard that my husband had left the Palace of Haarlem with the utmost secrecy accompanied by the general commanding the royal guard.

The general was a Frenchman, formerly an officer in my husband's old regiment of dragoons. He owed his promotion to my husband and was prepared to sacrifice his future on his behalf. The King had become aware that it was the Emperor's first intention to unite Holland to France.

The French armies dominated the country. It was impossible to think of opposing them. He therefore decided to withdraw. I cannot blame him for such a decision. On the contrary it is always a noble act to give up a throne on conscientious grounds.

Only I, who had never taken part in public affairs, could not help resenting the fact that I should have been forced to return to Holland in order to further his political schemes.

I received word that he had arrived at the resort of Toplitz. The only thing that prevented me from obeying my first impulse and hastening to him was the feeling that I was unable to help him in any way and the fear that my presence would recall the memories of a past when he had been unhappy.

Had I thought it was in my power to console him, I should not have hesitated. I should have put aside even the sacred interests of my children. But being convinced that my efforts would be useless, I felt that to go to my husband would be merely to appear to act generously toward him in the eyes of the world, and in reality, not better in any way the condition of the man for whom I was making this sacrifice.

The original French is available below: