Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

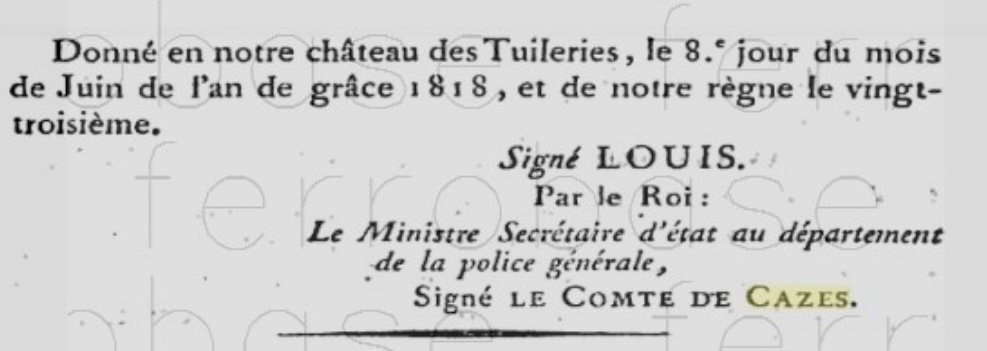

Monsieur Decazes enters the story. The following passage shows how this handsome and charming man guilted Hortense and then worked to harm her reputation. Like other obvious “assets” in this history, he just so happened to fair extraordinarily well after the fall of Napoleon.

Below we see what it looks like when someone is targeted and swarmed by nefarious agents. See if you can count how many agents are targeting Hortense in the paragraphs below.

I have learned that if that spy system is nudging me somewhere into a certain space or action then that direction is more than likely in my absolute worst interests. The key is in identifying their hidden hand and then knowing how to resist their irritating sneaky pressure. What they do feels wrong because it is wrong.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

The Emperor always considered subjects in their broad lines. The King on the contrary was only interested in minute details. A single idle phrase was enough to arouse his suspicion. He reflected as to what reasons might have prompted it, drew all sorts of conclusions from it and finally discovered a treasonable significance that had no basis other than the activity of his own imagination.

The result was that the majority of the Frenchmen whom he had taken to Holland with him were dismissed on account of something they had said, some doubt he had conceived in regard to their conduct.

Instead of being definitely dismissed, however, they were sent on special missions or received other posts, as for instance Monsieur de Caulaincourt, whom he appointed Ambassador to Naples. The others were shifted about: Monsieur d'Arjuzon, who had been the King's high chamberlain, became my first gentleman in waiting. Messieurs Devaux and de La Ville were appointed my equerries.

Consequently, in a short time I had so numerous a household that I did not know how to pay them all, especially as my income which I received from France was only that of a French princess.

Monsieur Decazes also arrived with a letter from my husband appointing him my private secretary. I had already Monsieur Despres, an elderly man who had been with me for a long time and with whom I was thoroughly satisfied. This was the only occasion on which I refused to carry out my husband's wishes in regard to my household. I had my reasons for doing so.

A few days before my departure from Cauterets, Monsieur Decazes, a fine-looking young man with excellent manners, arrived there. I received few visitors. He knew my reader and came to call on her.

Grief-stricken over the loss of his charming young wife, who had died after they had been married seventeen months, he was seeking some way of taking his mind off his sorrow.

The object of his journey made him a sympathetic figure to us. He asked to be presented to me and appeared so unhappy that I did not feel justified in refusing his request.

The day I met him he spoke of his wife, of his grief at losing her, and the need he felt of leaving France after such a shock. He wished me to obtain a post for him at my husband's court.

I suggested that he secure an introduction through his father-in-law, Monsieur Muraire, when he returned to Paris, and promised that I would also use my influence with the King. My trips into the mountains were just beginning at that time. I saw the young man only once more and then did not hear him mentioned again.

Monsieur Decazes' father-in-law, who was president of the Court of Cassation, presented him to my husband as I had suggested, and the King on our return to Paris from the Pyrenees appointed him his secretary and sent him off immediately to Holland.

I heard one day someone belonging to the Murat household say meaningly "The Queen of Holland saw a great deal of a certain young man while she was taking the waters and secured a post for him at her husband's court. That was very clever of her, I'm sure."

I could not imagine that this bit of spiteful gossip referred to anyone I knew as slightly as I did Monsieur Decazes and I paid no attention to it. But when Monsieur Decazes returned from Holland to assume the duties of my private secretary the remark came back to me and I declined to accept him.

The Queen of Naples one day when she was visiting me remarked: "Did you know that people are saying you have taken a fancy to that young man? I have had this repeated to me so many times that I wasn't sure myself about it, but I have just been watching you both, and I see there's nothing in the story. Nevertheless, he is both vain and a braggart, for Fouché tells me that he goes about saying he is on the best of terms with you."

Greatly astonished that the Chief of Police, instead of mentioning to me something that concerned me directly, should talk about it to persons who he knew would be only too glad to have reasons for criticizing me, I demanded that he explain such an absurd remark.

He seemed embarrassed, put the blame on the conceitedness of the young man, on the bad effect such gossip had on my reputation, even on the fact that it was he who had asked the Princess Caroline to warn me.

At last I became impatient with him for his evasions. On the other hand, how could I suspect the motives of Monsieur Decazes? I had only known him when bowed down with grief over the loss of his wife. Tears always make one think well of the person who sheds them. What reasons had I for believing that the sorrow of a stricken husband was a mask to conceal the vanity of a coxcomb?

Being still young I had not lost faith in the existence of frankness and loyalty. A too justifiable distrust of human nature had not yet made me critical and suspicious of people's motives. Moreover, Monsieur Decazes as a member of my husband's household must have known the King's character and been aware of our domestic difficulties, nor could there be any doubt that, like all Frenchmen living in Holland, he realized it was I who was in the right.

My misfortunes made everyone sympathize with me, and the public hesitated to condemn my behavior. In order to banish all doubts from my mind I thought it necessary to inform Monsieur Decazes of the remarks that were attributed to him. I expected that he would be deeply pained at such gossip.

He defended himself more or less vigorously, but when he realized that people might believe he had enjoyed my favors for even a short time, a satisfied smile showed that his vanity was rather flattered, and betrayed the true character of a man whom I had considered honorable simply because he happened to be in distress.

I admit that I was wrong in treating him in a manner he misinterpreted. After that he never appeared in my presence except when he came with messages from my husband. The King as soon as I refused to include Monsieur Decazes among my household granted him numerous favors.

Nevertheless, I soon learned the source of the various rumors that were being skillfully disseminated. In the pains taken to sully everything and everybody in any way connected with the Empress I recognized the hand of Fouché, one of the most ardent partisans of the Emperor's divorce.

To serve his ends it was necessary to discredit all the members of the family he sought to force into retirement. My brother's position was impregnable; but how was I to escape the intrigues of a minister so well placed to produce evidence in support of his accusations?

A woman in such cases is always helpless. The public knew the esteem the Emperor had for me. He had shown it on numerous occasions. In order to change his opinion of me and that of the general public nothing was simpler than to declare that I was involved in some entirely fictitious liaison.

This maneuver and many others were necessary in order that Fouché might have excuses for defending the idea of a divorce which France in general did not want.

My mother was too popular. She was too good, too generous, too amiable, too willing to listen to every appeal for help and to aid anyone who might be in trouble.

People could not dream of there being anyone kinder than she or imagine that a better or nobler person could exist. The public's affection was increased by the fear it had of losing her.

The Emperor, aware of this popularity, hesitated to secure a separation. It was in order to overcome his indecision that all sorts of schemes were set in operation. A great fuss was made about the Empress's enormous debts.

It was her kindness of heart that made her incur them and it was the poor who benefited by them. The knowledge of the extent of her generosity and the difficulties in which it involved her increased the public's affection for the Empress.

Only the Emperor, passionately fond of order, was pitiless in his condemnation of her conduct in this respect. The end of the year was always the most painful moment for my mother, crushed beneath the weight of debts that fell due then, debts which she had allowed to accumulate through fear of confessing to her husband the extent of her extravagance.

Having raged about them, the Emperor settled the debts. But the police found ways to revive his wrath by indicating that the Empress had only admitted half of the total of what she owed. Thus, by sowing the seeds of dissension they hoped to bring about a separation.

The original French is available below: