Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

This project is about what happens when someone just can’t take it anymore. Hortense also reached this moment when her son died. We all have our breaking point and what we do from then on is who we are.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

CHAPTER VII

THE DEATH OF THE PRINCE ROYAL TRAVELS IN SOUTHERN FRANCE (MAY-AUGUST 1807)

Illness and Death of the Prince Royal—A Mother's Agony—Change of Scene—The Pyrenees—Lourdes—Pau—Bayonne—Into Spain—Mountain Excursions—Return to Saint Cloud—The Emperor Rebukes Hortense—A Drive with Napoleon and Josephine—The Emperor's Opinion of the Rulers of Prussia and Russia.

ALAS! the moment was at hand when all my energy abandoned me. Not till then did I really know what it was to be unhappy, not yet had I experienced to the full the bitterness of grief, the sharpness of mental anguish.

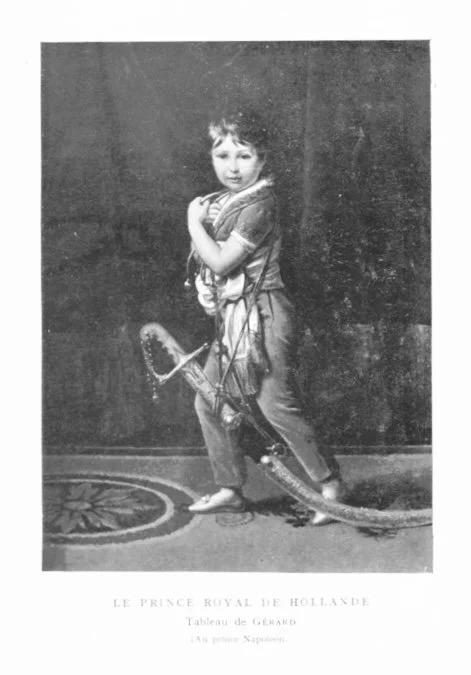

It was my child, my eldest son who had taught me how deeply I could love, who was to teach me these other lessons. My hand trembles as I tell the story and my tears flow while I write. I was at his bedside with his governess watching him while he slept. His breathing was irregular and oppressed; I could not take my eyes from him. Fear entered my soul. I prayed; I implored Providence to be just.

“My child must not die," I kept repeating. "What sin have I committed? For what offense am I being punished?"

My conscience reassured me. The foremost doctors in Holland were in attendance. My tears might disturb them, so I tried to be calm, to talk about my son's illness as though he were a stranger.

I felt that had I been in their place I should have found some remedy. Yet not one of them recognized the disease from which he was suffering. It was the croup. In two days, he died.

It was toward me that he turned his pale, wasted little face; it was I whom his lips scarcely able to utter a sound seemed to be calling; it was his mother's name that I saw framed on those discolored lips, and that passed with his last breath.

And I survived all this. How can God allow a mother to outlive her child? Other women, I know, have had sons and have lost them. But they doubtless had their family with them, or some friend, and were comforted and cared for, were relieved of at least a fraction of their despair. I was alone in the world, utterly alone with only my misfortune as companion.

My husband, overcome by his own grief, threw himself at the feet of his son, while I collapsed in so alarming a condition that every effort had to be made to revive me. I had uttered a piercing shriek when I saw that my son was lifeless. I lay in a swoon, as motionless as though I too were dead and yet hearing everything that went on about me.

The phrase, uttered by a doctor, "She gives no sign of life," was perhaps what brought me back to it. The hope of death made me resigned to the prospect of the hereafter. I was completely paralyzed and could not speak a word to those who wept beside my bed. My husband hastened to me, his face streaming with tears. He called my name, implored me to keep on living for his sake and to forgive him the sorrows and unfair treatment he had inflicted on me.

For the first time in his life he admitted he had done wrong. I remained insensible; no emotion stirred within me. My only thought was the prospect of a speedy death. "I am about to die," I said to myself. The despair of those about me proved this. It gave me a welcome certitude of my approaching end which comforted me and removed some of the weight of despair beneath which I was crushed.

This state lasted several hours. My window was open. The mournful song of the watchmen calling the hours of night came to my ears. I cannot describe the effect it had on me. I made a movement which betrayed the fact that I was still alive, but how little I cared for that life.

The following day passed, dreary and silent. I could not shed a tear. They brought me the child that was left me. I looked at him, then pushed him away. "I do not want to love anything again on earth."

I felt I was about to die and I waited impatiently for the hour to strike. Religion might have succored me, but at that moment I did not respond to any religious sentiment; all those emotions seemed to have been stifled in my heart.

For what am I being punished? What have I done wrong? Was I not already unhappy enough? I can no longer believe in God, in his kindness or in his justness, but if I die, then my faith in Him will be restored," I exclaimed.

I added a moment later: "I feel He has set a limit for my sufferings. He is about to reunite me to my son. Now may His name be praised!”

I yearned for that moment to come. None of these thoughts changed my physical condition. My body had lost the power to move, my eyes were always dry and with a fixed stare in them, my features unchanging and expressionless. I was no longer in communication with those about me. I showed no apparent sign of being alive, only my inner life still continued.

The doctors recommended that I should travel. I made no objections, for nothing any longer affected me. It had been difficult to make me take any nourishment.

A new novel that had just appeared was read aloud to me. Everything was done to distract my attention, which seemed concentrated unremittingly on a single point. The words uttered near me reached my brain but were unable to distract my mind. I had constantly before my eyes the lifeless body of my son and was unable to shed a tear. Princess Caroline hastened to me from Paris as well as Adele and her sister, the wife of Marshal Ney.

Far from being touched by this token of their affection, I looked at them without saying a word. I knew that they were my friends, but I had ceased to care for anyone. My mother came to the Château of Laeken to which I was taken.

She was overcome with grief at the death of her grandson, yet found courage enough to come and nurse her daughter. In what a state she found me! Much had been hoped from our meeting. It was thought the presence of my beloved mother would produce a beneficial emotion.

On my arrival at the palace of Laeken the Empress in tears rushed forward to meet me. I recognized her perfectly, looked at her, but not a word or sign indicated that I still retained a spark of affection for her.

She had not conceived a condition which no remedy could cure; the sight of me filled her with alarm and grief. Doctor Corvisart declared that only the passage of time and change of scene could improve my health and that drugs would kill me.

His opinion was followed, and I was surprised to hear my husband approve of it. "Is it possible he agrees to something that will do me good? It is the first time he has ever done a thing like that."

If anything could have moved me it would have been this change in Louis' attitude. That was why when he left me to return to Holland, I took his hand and said: "Louis, I feel that I am about to die. I wish to give you the assurance that I forgive you; I die as innocent as the child I have just lost.

Wherever he may be, I shall be by his side. Do not grieve on my account, for I shall be happy." He begged me to take care of myself, not to give way to such sad premonitions, and left the palace. My mother took me out for daily walks to visit the neighboring estates. It did not matter to me where we went; I had no preferences, no will of my own.

Nevertheless, the presence of many people made me feel noticeably ill at ease. One day we were at one of these estates. The owners paid us a thousand compliments, to which I did not reply a single word. Indeed, I felt so annoyed that I took a path that led away from that which the rest of the gathering were following.

The original French is available below: