I’m trying to show that what’s been happening to me also happened to courageous lone wolf journalist Elias Demetracopoulos. We keep losing our rights because we keep allowing foreign infiltrators to take them.

Please note that after the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, it just so happens that Heinz “Henry” Kissinger slipped right into inhabiting a central role of unelected authority over the United States of America and then he proceeded to “advise” all of the presidents from then on.

It is interesting that the brother of these assassinated Kennedy men, Senator Edward Kennedy, warned Elias Demetracopoulos that there was yet another assassination in the works.

I’m trying to show you the person I presume to be our nation’s not so hidden dictator. Am I making my case?

It’s like this because we are allowing it. We must change if we want this tyranny to change.

The following relates to the efforts of Kissinger’s coterie to silence journalist Elias Demetracopoulos. The text below is continued from here.

The cable was addressed, as is usual from an ambassador, to Secretary of State William Rogers. Yet it was also addressed-highly unusually-to Attorney General John Mitchell. But Mitchell, as we have seen, was the only attorney general ever to serve on Henry Kissinger's supervisory Forty Committee, which oversaw covert operations.

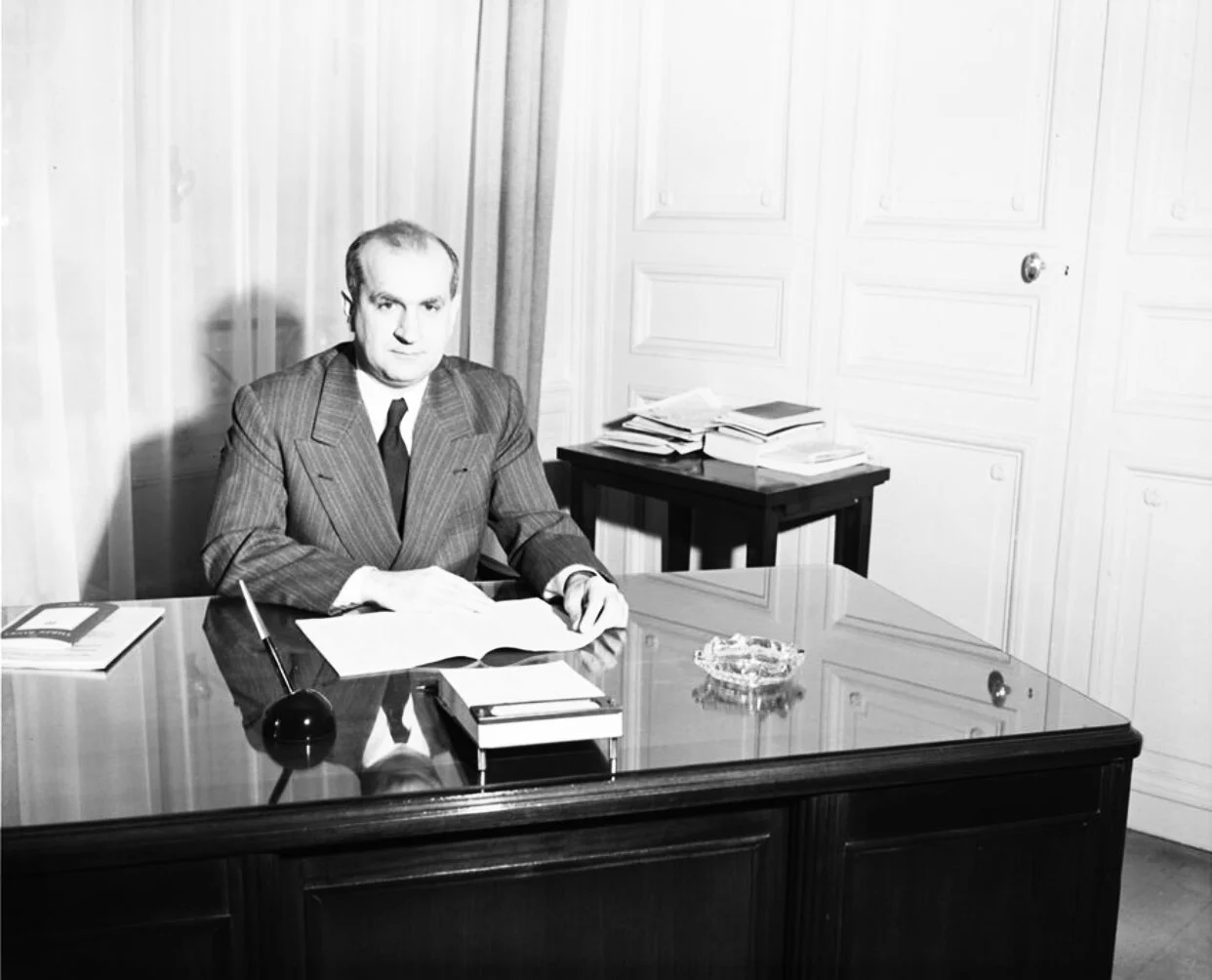

Attorney General John Mitchell

The State Department duly urged that "the Department of Justice do everything possible to see if we can make a Foreign Agent's case, or any kind of a case for that matter" against Demetracopoulos.

Of course, as was later admitted, these investigations turned up nothing. The influence wielded by Demetracopoulos did not derive from any sinister source or nexus.

But when he said that the Greek dictatorship had trampled its own society, used censorship and torture, threatened Cyprus, and bought itself political influence in Washington, he was uttering potent factual truths.

Nixon himself confirmed the connection, between the junta and Pappas and Tasca and the two-way flow of dirty money, on a post-Watergate White House tape dated 23 May 1973. He is talking to his renowned confidential secretary, Rose Mary Woods: Good old Tom Pappas, as you probably know or heard, if you haven't already heard, it is true, helped, at Mitchell's request, fund-raising for some of the defendants.... He came up to see me on March 7, Pappas did. Pappas came to see me about the ambassador to Greece, that he wanted to-he wanted to keep Henry Tasca there.

This same dictatorship had in June 1970 revoked Demetracopoulos's Greek citizenship, so he was a stateless person traveling only on a flimsy document giving him leave to re-enter the United States.

This fact assumed its own importance in December 1970, when his blind father was dying of pneumonia, alone, in Athens. Demetracopoulos sought permission to return home under a safe-conduct or laissez-passer, and was able to enlist numerous congressional friends in the attempt.

Among them were senators Frank E. Moss of Utah, Quentin N. Burdick of North Dakota, and Mike Gravel of Alaska, who signed a letter dated 11 December to the Greek government and to Ambassador Tasca. Senators Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts and William Fulbright of Arkansas also expressed a personal interest.

Senator Frank E. Moss of Utah

Neither the Athens regime nor Tasca replied directly, but on 20 December, four days after the old man had died without a visit from his only son, Senators Moss, Burdick, and Gravel received a telegram from the Greek embassy in Washington.

This instructed them that Demetracopoulos should have applied in person to the embassy: an odd demand to make of a man whose passport and citizenship had just been canceled by the dictatorship.

Meanwhile, Demetracopoulos received a telephone call at his home, from Senator Kennedy in person, advising him not to accept any safe-conduct offer from Greece even if he was offered it.

Had Demetracopoulos presented himself at the junta's embassy, he might well have been detained and kidnapped, in accordance with one of the plans we now know had been readied for his "disappearance."

Of course, such a scheme would have been extremely difficult to carry out in the absence of some "cooperation"-at least a blind eye–from local US intelligence officials.

Senator Mike Gravel of Alaska

Declassified cable traffic between Ambassador Tasca in Athens and Kissinger's deputy Joseph Sisco at the State Department shows that Senator Kennedy's misgivings were amply justified.

In a cable dated 14 December from Sisco to Tasca, the ambassador was told: “If GOG [Government of Greece] permits Demetracopoulos to enter, quite clearly we must avoid being put in a position of guaranteeing any assurances that he may have of being able to depart."

Concurring with this extraordinary statement, Tasca added that there was a possibility of Senator Gravel attending the funeral of Demetracopoulos senior.

Ambassador Henry J. Tasca

Elias, wrote the ambassador, "undoubtedly hopes to exploit Senator's visit by providing some way of proving that conditions here are as repressive as he has been representing them to be. He could even try to arrange for some manifestation of violence, such as a small bomb."

The absurdity of this-Demetracopoulos had no record whatever of the advocacy or practice of violence, as Tasca subconsciously recognized by making the hypothetical bomb a “small" one-also has its sinister side.

Suggested here is just the sort of alibi or provocation or pretext that the junta might need for a frame-up, or to cover up a "disappearance."

The entire correspondence reeks of the unspoken priorities of both the embassy and the State Department, which reflect their contempt for elected United States senators, their dislike of dissent, and their need to gratify a group of Greek gangsters who are now rightly serving terms of life imprisonment.