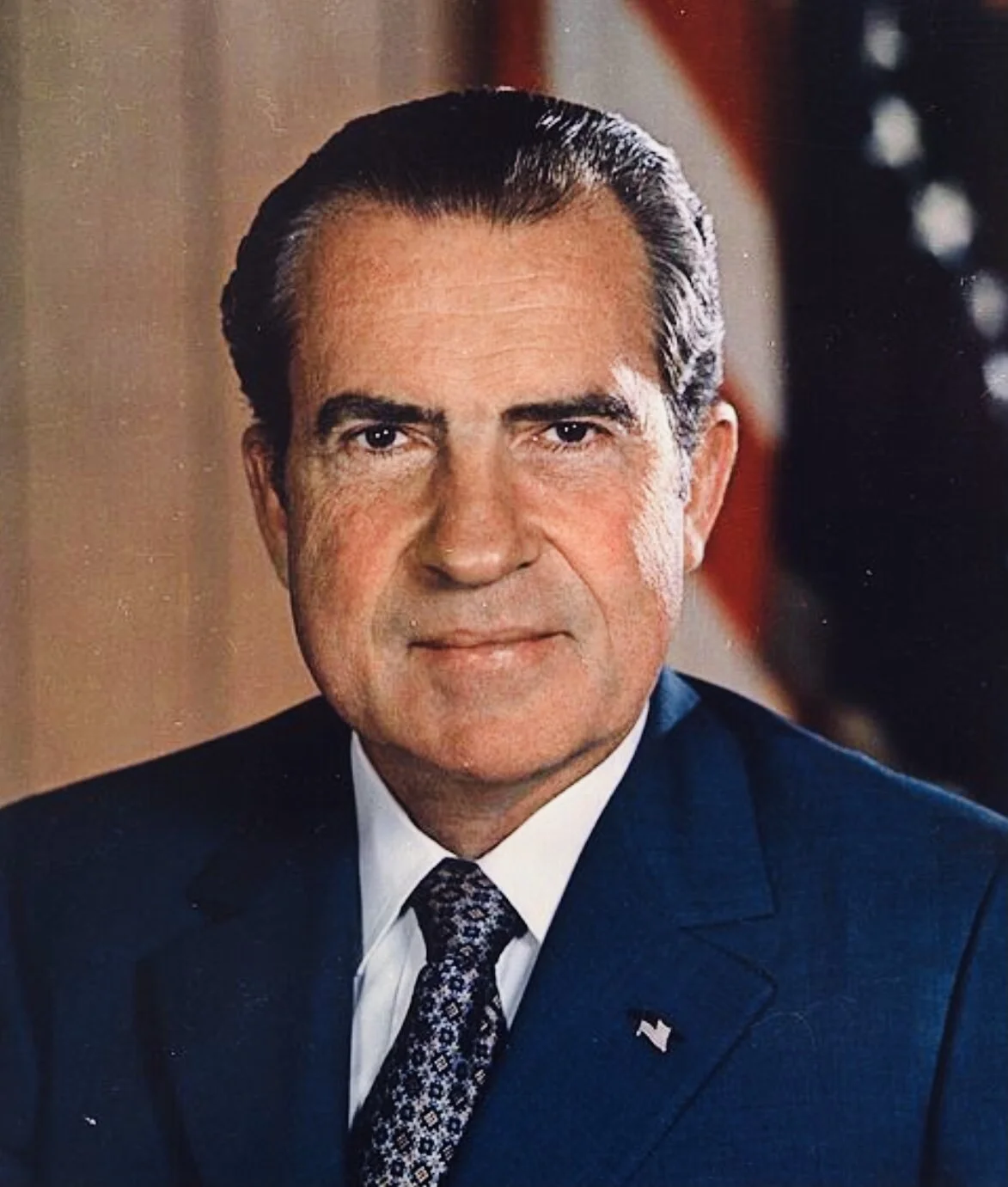

We can see below the destabilizing work employed against Chile. The group who have hijacked authority are extremely easy to identify by their patterns.

Christopher Hitchens continues telling about how a “hit” was ordered against Chilean General René Schneider.

3. Look again at the White House/Kissinger memo of 15 October, and at the doggedly literal way it is retransmitted to Chile. In no sense of the term does it "turn off" Viaux. If anything, it incites him-a well-known and boastful fanatic-to redouble his efforts. "Preserve your assets. We will stay in touch. The time will come when you together with all your other friends can do something. You will continue to have our support."

President Salvador Allende

This is not exactly the language of standing him down. The remainder of the memo speaks plainly of the intention to "discourage him from acting alone," and to "continue to encourage him to amplify his planning" and to “encourage him to join forces with other coup planners so that they may act in concert either before or after 24 October" (italics added).

The last three stipulations are an entirely accurate, not to say prescient, description of what Viaux actually did.

4. Consult again the cable received by Henry Hecksher on 20 October, referring to anxious queries "from high levels" about the first of the failed attacks on Schneider. Thomas Karamessines, when questioned by the Senate Intelligence Committee about this cable, testified of his certainty that the words “high levels" referred directly to Kissinger. In all previous communications from Washington, as a glance above will show, that had indeed been the case. This on its own is enough to demolish Kissinger's claim to have "turned off" Track Two (and its interior tracks) on 15 October.

Financial warfare against humanity is nothing new for this regime.

5. Ambassador Korry later made the obvious point that Kissinger was attempting to build a paper alibi in the event of a failure by the Viaux group. “His interest was not in Chile but in who was going to be blamed for what. He wanted me to be the one who took the heat. Henry didn't want to be associated with a failure and he was setting up a record to blame the State Department. He brought me in to the President because he wanted me to say what I had to say about Viaux; he wanted me to be the soft man."

Edward M. Korry (right) with President John F. Kennedy, 1963 Korry, a native of New York, was U.S. Ambassador to Ethiopia (1963-1967) and to Chile (1967–1971). Upon hearing the news that Salvador Allende had been elected president of Chile, he proclaimed that "not a nut or bolt shall reach Chile under Allende. Once Allende comes to power we shall do all within our power to condemn Chile and all Chileans to utmost deprivation and poverty".[2]

The concept of “deniability" was not as well understood in Washington in 1970 as it has since become.

Ambassador Korry

But it is clear that Henry Kissinger wanted two things simultaneously. He wanted the removal of General Schneider, by any means and employing any proxy. (No instruction from Washington to leave Schneider unharmed was ever given; deadly weapons were sent by diplomatic pouch, and men of violence were carefully selected to receive them.)

And he wanted to be out of the picture in case such an attempt might fail, or be uncovered.

These are the normal motives of anyone who solicits or suborns murder.

However, Kissinger needed the crime very slightly more than he needed, or was able to design, the deniability.

Without waiting for his many hidden papers to be released or subpoenaed, we can say with safety that he is prima facie guilty of direct collusion in the murder of a democratic officer in a democratic and peaceful country.

There is no particular need to rehearse the continuing role of the Nixon-Kissinger administration in the later economic and political subversion and destabilization of the Allende government, and in the creation of favorable conditions for the military coup that occurred on 11 September 1973.

This regime’s preference for Chile.

Kissinger himself was perhaps no more and no less involved in this effort than any other high official in Nixon's national-security orbit. On 9 November 1970 he authored the National Security Council's "Decision Memorandum 93," reviewing policy toward Chile in the immediate wake of Allende's confirmation as President.

Various routine measures of economic harassment were proposed (recall Nixon's instruction to “make the economy scream") with cutoffs in aid and investment.

More significantly, Kissinger advocated that "close relations" be maintained with military leaders in neighboring countries, in order to facilitate both the coordination of pressure against Chile and the incubation of opposition within the country. In outline, this prefigures the disclosures that have since been made about Operation Condor, a secret collusion between military dictatorships across the hemisphere, operated with United States knowledge and indulgence.

The actual overthrow of the Allende government in a bloody coup d'état took place while Kissinger was going through his own Senate confirmation process as Secretary of State.

He falsely assured the Foreign Relations Committee that the United States government had played no part in the coup. From a thesaurus of hard information to the contrary, one might select Situation Report #2, from the Navy Section of the United States Military Group in Chile, and written by the US Naval Attaché, Patrick Ryan.

Ryan describes his close relationship with the officers engaged in overthrowing the government, hails 11 September 1973 as "our D-Day" and observes with satisfaction that "Chile's coup de etat [sic] was close to perfect."

Or one may peruse the declassified files on Project FUBELT–the code name under which the CIA, in frequent contact with Kissinger and the Forty Committee, conducted covert operations against the legal and elected government of Chile.

![Edward M. Korry (right) with President John F. Kennedy, 1963 Korry, a native of New York, was U.S. Ambassador to Ethiopia (1963-1967) and to Chile (1967–1971). Upon hearing the news that Salvador Allende had been elected president of Chile, he proclaimed that "not a nut or bolt shall reach Chile under Allende. Once Allende comes to power we shall do all within our power to condemn Chile and all Chileans to utmost deprivation and poverty".[2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55161913e4b04038107de5a2/1621791944468-NJGZZZXDHGP2YX036YRV/IMG_4908.jpeg)