Is the following what happens when the depopulation enthusiast crowd are put in charge of health and housing policy funded by taxpayers? If all the arrows point in one direction, there is a reason for that.

Meanwhile, connected businessmen continued to reap benefits from the reconstruction efforts. For contracts to remove debris in Port-au- Prince, USAID went with Washington-based CHF International.

As Rolling Stone put it, CHF became "one of the largest USAID contractors in Haiti and enjoys a cozy relationship with Washington."

It turns out that the company's CEO, David Weiss, had been the deputy US trade representative for North American affairs during the Clinton administration. (He was also a 2008 Hillary for President campaign contributor.)

In addition, the corporate secretary of the board of directors is Lauri Fitz-Pegado, who was a protégé of Clinton commerce secretary Ron Brown. Fitz-Pegado had served in a series of positions in the Clinton White House, including assistant secretary of commerce.

CHF received particular scorn from journalists on the ground in Haiti. According to Rolling Stone, the firm operated out of "two spacious mansions in Port-au-Prince and maintains a fleet of brand-new vehicles, [and] is generally considered one of the most ostentatious" groups working out of Haiti.

USAID contracts also went to consulting firms like New York-based Dalberg Global Development Advisors, which was also an active participant in and financial supporter of CGI. In spring 2010 Dalberg received a $1.5 million contract to identify relocation sites for Haitians displaced by the quake from their homes and communities.

No one is above the law

USAID's inspector general reviewed the firm's recommendations and found them generally sloppy and unusable. As Rolling Stone reported, "One of the sites they said was habitable was actually a small mountain.... It had an open-sided pit on one side of it, a severe 100 foot cliff, and ravines.... It became clear that these people may not even have gotten out of their SUVS."

One early initiative pushed by both Bill and Hillary was to provide transitional housing for those left homeless by the earthquake.

The plan was to give grants and funds to build approximately twenty thousand temporary shelters for $138 million. But nearly a year later, an April 19, 2011, audit by the USAID Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found that only 22 percent of the shelters had been built and that many of those were "substandard."

The results were no better when it came to providing new permanent homes. In December 2010 Bill and Hillary approved a “new settlements program" that called for fifteen thousand homes to be built in and around Port-au-Prince. But by June 2013, more than two and a half years later, the GAO audit revealed that only nine hundred houses had been built.

The goal was subsequently cut to twenty-six hundred. At the same time, the cost of the project almost doubled, from $53 million to $90 million. Even projects run through the Clinton Foundation and not the federal government achieved disastrous results.

When Bill decided that the United States needed to secure temporary housing for Haitian schoolchildren (a legitimate priority), Clayton Homes approached the Clinton Foundation and offered to help.

The company was still in trouble with the Federal Emergency Management Agency for sending thousands of bad trailers to the US Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina.

A class action brought against Clayton Homes and others was eventually settled. In Haiti the Clinton Foundation paid $4 million of private money for what were called "hurricane proof trailers" that were "structurally unsafe," and in some instances were found to have high levels of formaldehyde, with insulation coming out of the walls.

The fumes, mold problems, and stifling heat made students sick. Many trailers ended up abandoned because they were poorly designed and ill suited to the Haitian climate.

From Chappaqua, New York, Bill dreamed up the idea of a housing expo in Haiti that would bring architects and design firms from around the world to create sustainable homes using composite materials.

The project was dubbed Building Back Better Communities (BBBC). Each builder erected a sample home for Haitians to live in. These buildings and designs were expected to be adopted for widespread use in the earthquake-ravaged country.

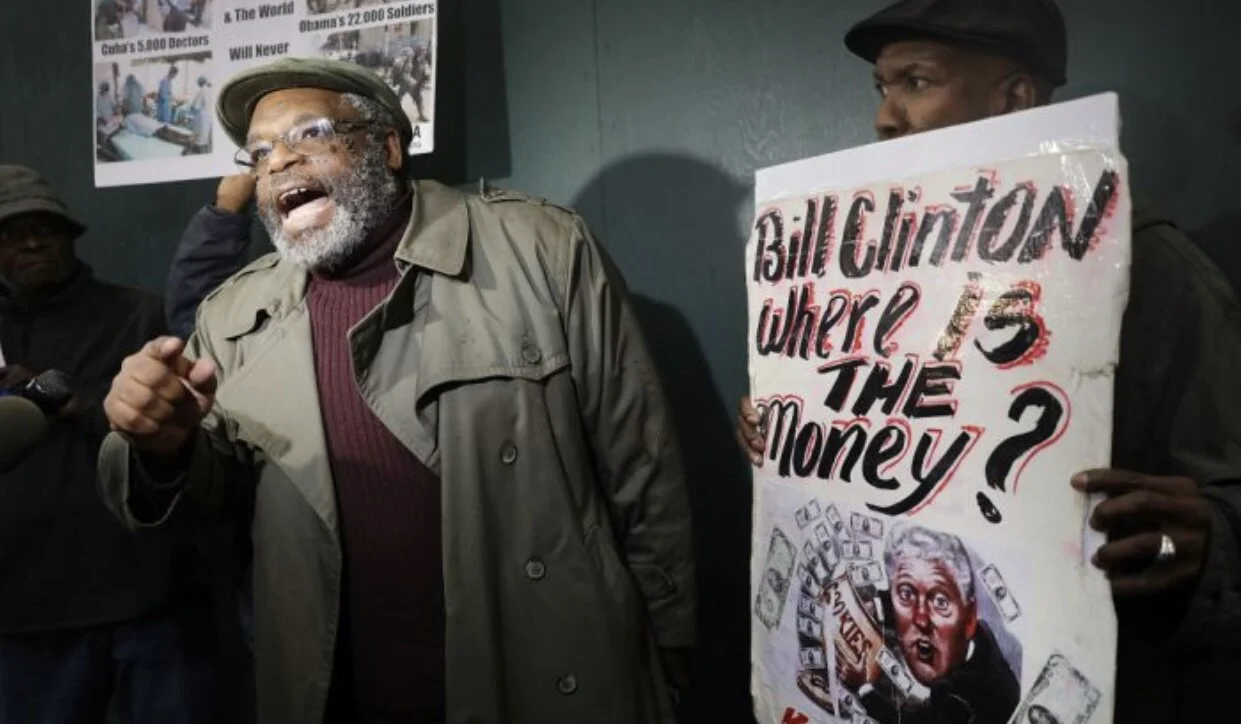

How can the same group get so many angry all over the world? The link is here.

But fourteen months later, “most of the model homes sat empty," providing shelter for squatters and the occasional goat. "It was a waste of money with no respect for the builders," Gabriel Rosenberg of GR Construction, a Haitian firm, said in a telephone interview. "We invested about 25,000 dollars. We expected to sell those houses."

"It was the biggest joke I've ever seen," complained John Sorge, with the firm Innovative Composites International (ICI). “It was a hoodwink to promote the government ... the whole Expo was a farce." By far the largest and most ambitious project for Hillary and Bill was their plan to build a clothing factory in northern Haiti.

The link is here.

The area had been untouched by the earthquake, but they authorized the use of US taxpayer funds for rebuilding to create what would be called the Caracol Industrial Park.

The Clintons had actually been pushing this project for some time. Cheryl Mills, Hillary's right hand at State, was "credited with leading the effort for more than a year," wrote the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Originally a straightforward plan for economic development, the project gained new momentum as a means to both uplift the Haitian economy and house homeless workers. In the end, the complex project required hundreds of millions in US taxpayer money and special legislation passed through Congress granting tariff-free access to US markets.