My real harassers have been hiding behind various agents, many of which have been exposed over the last few years. Who sent them? How much money has been spent sending me tricksters and infiltrators?

You are reading my trial against my hidden harassers and Christopher Hitchens is my witness. Since my harassers are so very secretive, I must establish the identity of my hidden harassers through their patterns on behavior.

With slight differences of emphasis, the larger pieces of this story appear in Haldeman's work as cited, and in Clifford's memoir.

They are also partially rehearsed in President Johnson's autobiography The Vantage Point, and in a long reflection on Indochina by William Bundy (one of the architects of the war) entitled rather tritely The Tangled Web.

Senior members of the press corps, among them Jules Witcover in his history of 1968, Seymour Hersh in his study of Kissinger, and Walter Isaacson, editor of Time magazine, in his admiring but critical biography, have produced almost congruent accounts of the same abysmal episode.

And I was awake back then.

Kissinger is like the Evil horror movie character that just won't stop, can't be stopped. He should never be allowed as an "advisor" to any government or government agency. He should never be interviewed as an "expert" on government affairs again. He is an expert at hypnotizing only too willing government officials to act against humanity.

I myself parsed The Haldeman Diaries in The Nation in 1994. The only mention of it that is completely and utterly false, and false by any literary or historical standard, appears in the memoirs of Henry Kissinger himself.

Haldeman

He [Haldeman] writes just this: Several Nixon emissaries-some self- appointed-telephoned me for counsel. I took the position that I would answer specific questions on foreign policy, but that I would not offer general advice or volunteer suggestions. This was the same response I made to inquiries from the Humphrey staff.

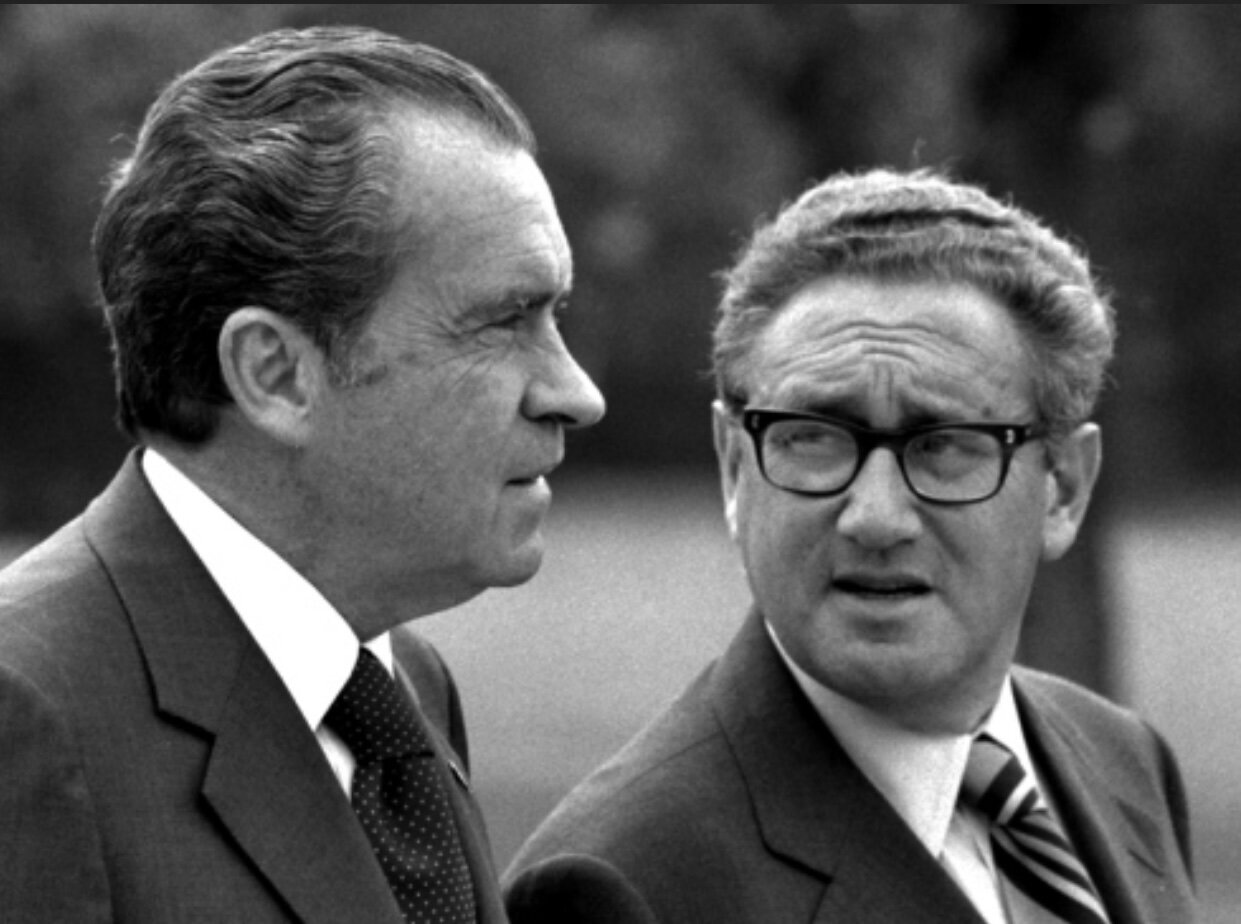

This contradicts even the self-serving memoir of the man who, having won the 1968 election by these underhand means, made as his very first appointment Henry Kissinger as National Security Advisor. One might not want to arbitrate a mendacity competition between the two men [Haldeman and Nixon], but when he made the choice to hire Kissinger, Richard Nixon had only once, briefly and awkwardly, met Henry Kissinger in person.

He clearly formed his estimate of the man's abilities from more persuasive experience than that. "One factor that had most convinced me of Kissinger's credibility," Nixon wrote later in his own delicious prose, "was the length to which he went to protect his secrecy."

But that ghastly secret is now out. In the December 1968 issue of the establishment organ Foreign Affairs, written months earlier but published a few days after his gazetting as Nixon's right-hand man, there appeared Henry Kissinger's own evaluation of the Vietnam negotiations.

On every point of house substance, he agreed with the line taken in Paris by the Johnson-Humphrey negotiators. One has to pause for an instant to comprehend the enormity of this.

Kissinger had helped elect a man who had surreptitiously promised the South Vietnamese junta a better deal than they would get from the Democrats. The Saigon authorities then acted, as Bundy ruefully confirms, as if they did indeed have a deal.

This meant, in the words of a later Nixon slogan, "Four More Years."

But four more years of an unwinnable and undeclared and murderous war, which was to spread before it burned out, and was to end on the same terms and conditions as had been on the table in the fall of 1968.

This was what it took to promote Henry Kissinger. To promote him from being a mediocre and opportunist academic to becoming an international potentate.

The signature qualities were there from the inaugural moment: the sycophancy and the duplicity; the power worship and the absence of scruple; the empty trading of old non-friends for new non-friends.

And the distinctive effects were also present: the uncounted and expendable corpses; the official and unofficial lying about the cost; the heavy and pompous pseudo-indignation when unwelcome questions were asked.

Kissinger's global career started as it meant to go on. It debauched the American republic and American democracy, and it levied a hideous toll of casualties on weaker and more vulnerable societies.

By Way of Warning: A Brief Note on the 40 Committee In many of the ensuing pages and episodes, I've found it essential to allude to the “40 Committee" or the "Forty Committee," the semi-clandestine body of which Henry Kissinger was the chairman between 1969 and 1976.

One does not need to picture some giant, octopuslike organization at the center of a web of conspiracy: however, it is important to know that there was a committee which maintained ultimate supervision over United States covert actions overseas (and, possibly, at home) during this period.

The CIA was originally set up by President Harry Truman at the beginning of the Cold War. In the first Eisenhower administration, it was felt necessary to establish a monitoring or watchdog body to oversee covert operations.

This panel was known as the Special Group, and sometimes also referred to as the 54/12 Group, after the number of the National Security Council directive which set it up.

Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973.

By the time of President Johnson it was called the 303 Committee and during the Nixon and Ford administrations it was called the 40 Committee.

Some believe that these changes of name reflect the numbers of later NSC directives; in fact the committee was known by the numbers of the successive rooms in the handsome Old Executive Office Building (now annexed to the neighboring White House) which used to shelter the three departments of "State, War and Navy," in which it met. No mystery there.