THE LOGAN ACT OF 1799 prohibits unauthorized American citizens from negotiating with foreign governments.

The professor's conclusion here is arguably too tentative. There is a well-understood principle known as “Mutual Assured Destruction," whereby both sides possess more than enough material with which to annihilate the other.

The answer to the question of what the Johnson administration "had" on Nixon is a relatively easy one. It was given in a book entitled Counsel to the President, published in 1991. Its author was Clark Clifford, the quintessential blue-chip Washington insider, who was assisted in the writing by Richard Holbrooke, the former Assistant Secretary of State and Ambassador to the United Nations. In 1968, Clark Clifford was Secretary of Defense and Richard Holbrooke was a member of the United States negotiating team at the Vietnam peace talks in Paris.

From his seat in the Pentagon, Clifford had actually been able to read the intelligence transcripts that picked up and recorded what he terms a “secret personal channel" between President Thieu in Saigon and the Nixon campaign.

John Mitchell

The chief interlocutor at the American end was John Mitchell, then Nixon's campaign manager and subsequently Attorney General (and subsequently Prisoner Number 24171-157 in the Alabama correctional system).

He was actively assisted by Madame Anna Chennault, known to all as The Dragon Lady. A fierce veteran of the Taiwan lobby, and all-purpose right-wing intriguer, she was a social and political force in the Washington of her day and would rate a biography on her own.

Clifford describes a private meeting at which he, President Johnson, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and National Security Advisor Walt Rostow were present.

Hawkish to a man, they kept Vice President Humphrey out of the loop. But, hawkish as they were, they were appalled at the evidence of Nixon's treachery. They nonetheless decided not to go public with what they knew.

Clifford says that this was because the disclosure would have ruined the Paris talks altogether. He could have added that it would have created a crisis of public confidence in United States institutions.

There are some things that the voters can't be trusted to know.

And, even though the bugging had been legal, it might not have looked like fair play. (The Logan Act prohibits any American from conducting private diplomacy with a foreign power, but it is not very rigorously or consistently enforced.)

In the event, Thieu pulled out of the negotiations anyway, ruining them just two days before the election. Clifford is in no doubt of the advice on which he did so: The activities of the Nixon team went far beyond the bounds of justifiable political combat.

It constituted direct interference in the activities of the executive branch and the responsibilities of the Chief Executive, the only people with authority to negotiate on behalf of the nation.

The activities of the Nixon campaign constituted a gross, even potentially illegal, interference in the security affairs of the nation by private individuals.

Perhaps aware of the slight feebleness of his lawyerly prose, and perhaps a little ashamed of keeping the secret for his memoirs rather than sharing it with the electorate, Clifford adds in a footnote: It should be remembered that the public was considerably more innocent in such matters in the days before the Watergate hearings and the 1975 Senate investigation of the CIA.

Perhaps the public was indeed more innocent, if only because of the insider reticence of white-shoe lawyers like Clifford, who thought there were some things too profane to be made known.

He claims now that he was in favor either of confronting Nixon privately with the information and forcing him to desist, or else of making it public. Perhaps this was indeed his view.

A more wised-up age of investigative reporting has brought us several updates on this appalling episode. And so has the very guarded memoir of Richard Nixon himself. More than one “back channel" was required for the Republican destabilization of the Paris peace talks.

There had to be secret communications between Nixon and the South Vietnamese, as we have seen. But there also had to be an informant inside the incumbent administration's camp-a source of hints and tips and early warnings of official intentions.

That informant was Henry Kissinger.

In Nixon's own account, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, the disgraced elder statesman tells us that, in mid-September 1968, he received private word of a planned “bombing halt."

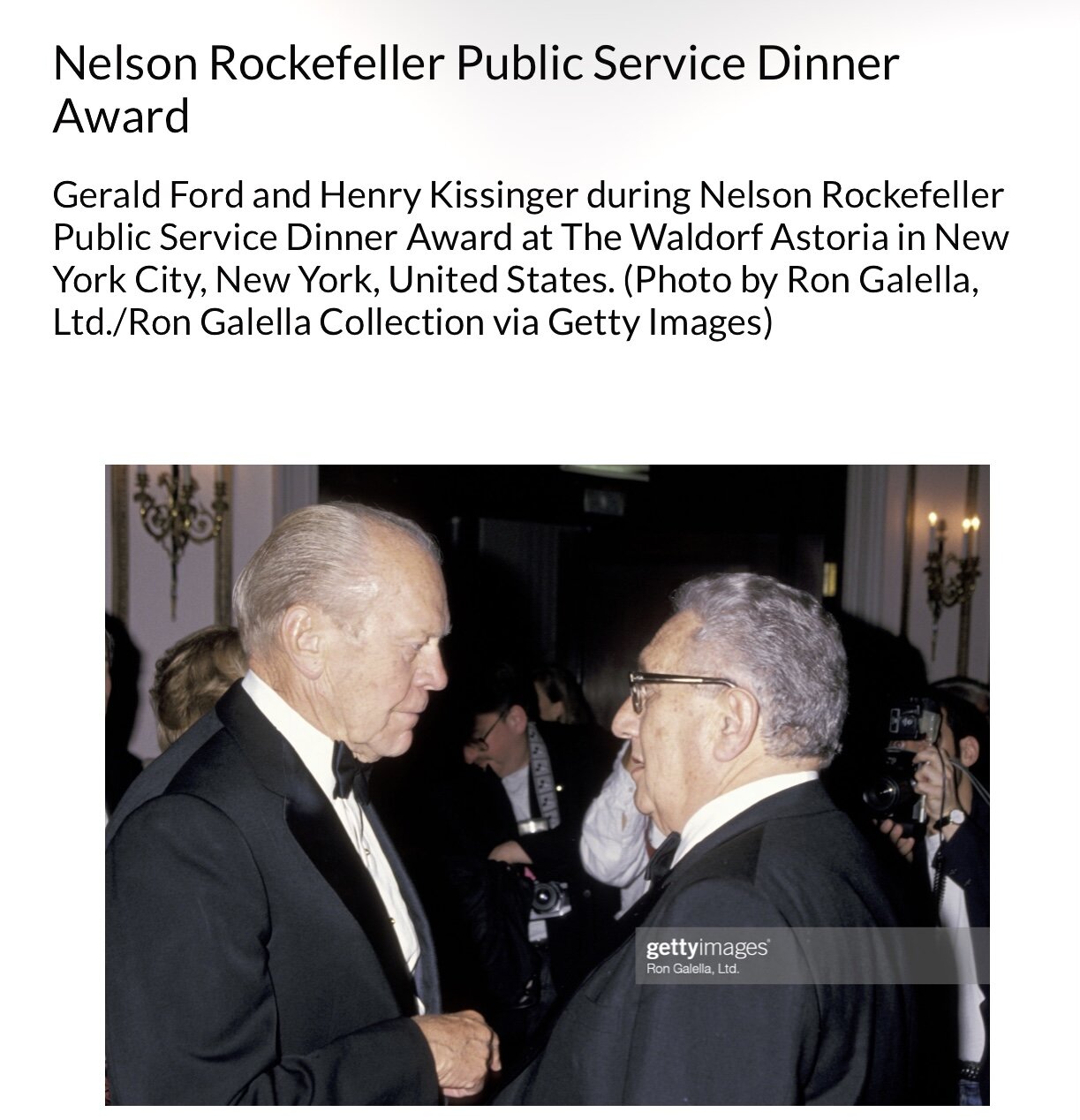

Nelson Rockefeller, second from left.

In other words, the Johnson administration would, for the sake of the negotiations, consider suspending its aerial bombardment of North Vietnam. This most useful advance intelligence, Nixon tells us, came "through a highly unusual channel."

It was more unusual even than he acknowledged. Kissinger had until then been a devoted partisan of Nelson Rockefeller, the matchlessly wealthy prince of liberal Republicanism.

His contempt for the person and the policies of Richard Nixon was undisguised. Indeed, President Johnson's Paris negotiators, led by Averell Harriman, considered Kissinger to be almost one of themselves.

He had made himself helpful, as Rockefeller's chief foreign policy advisor, by supplying French intermediaries with their own contacts in Hanoi.

"Henry was the only person outside of the government we were authorized to discuss the negotiations with," says Richard Holbrooke.

Richard Holbrooke

"We trusted him. It is not stretching the truth to say that the Nixon campaign had a secret source within the US negotiating team."