We continue here with Kissinger lobbying for “crony capitalism”. The author, Christopher Hitchens, also describes receiving himself the kind of “helpful attention” and the SAME EXACT pattern of behavior I’ve been describing publicly since I started talking about the NXIVM operation which led to me becoming blacklisted.

I’ve also gotten a lot of organized crime style attention at my house. I believe I know who has been harassing me, I’m trying to convince to my readers about the identities of these individuals.

This is my trial [against the suspected individuals who appear to be suing me behind a guy obviously lacking in funds] as well. They may have what seems like all the money in the world to harass me but I have the truth on my side.

Christopher Hitchens continues:

The same memorandum shows that the talk then turned to Indonesia's oil policy, and to Suharto's complaint that major petroleum corporations shared more of the wealth with their Middle Eastern partners than they did with Indonesia.

Suharto

Expressing sympathy for his attempt to negotiate a better deal, Kissinger found time to warn the despot that, whatever he did, he should "not create a climate that discourages investment."

William Rogers

This was a case of pushing at an open door: to the very end of his regime Suharto maintained an investment-friendly climate, at least for a certain class of cronies of whom, perhaps coincidentally, Kissinger eventually became one.

Indeed, Indonesian “crony capitalism" and its practitioners became a major element in the scandal of United States campaign finance, and of the Congressional investigation into it, that marked the Clinton years. Kissinger even hired Clinton's former White House Chief of Staff Mack McLarty as a partner in Kissinger Associates, and it may not be fanciful to suppose that the Indonesian connection played a role in this beautiful piece of bipartisanship.

The Suharto regime collapsed and imploded between the years 2000 and 2001. East Timor won its independence, and Indonesia formally withdrew its claim to the territory.

Suharto himself was indicted by the Indonesian courts for corruption and only escaped the verdict by resorting, as had General Pinochet, to the claim of mental and physical incompetence.

Suharto

Once again, though, the senior partner in the massacres and in the corruption managed to escape condemnation.

Washington

As I was preparing to publish the original version of this book, I received a call from William Rogers. Mr. Rogers is a partner in the distinguished Washington law firm of Arnold and Porter and was, during Kissinger's period as Secretary of State, the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs.

Pretending to help.

He is also a cog in the wheel of Kissinger Associates. Someone had leaked the advance news of publication to a New York newspaper and Mr. Rogers, on first contact, was all friendliness. Could he help? He wanted to know. I told him that I had already forwarded a request for an interview to his boss, and had mentioned the headings - Chile, Timor, Bangladesh and the Demetracopoulos affair-which I hoped to discuss with him.

Mr. Rogers professed astonishment at the fourth of these topics. "Who is this guy Demetra-whatsisname?" he inquired.

Pretending to not notice inconvenient people.

"We've never heard of him." He then asked me to send a list of all my questions, in order that he might be more “helpful" still. Recognizing a fishing expedition when I saw one, I instead wrote again to Kissinger offering to pay him for his trouble and proposing that, if he would give me and Harper's magazine half an hour on the record, we would pay him at the same rate offered by ABC News Nightline. (I did not add that, for this honorarium, we would ask him all the questions he has never been asked by Mr. Ted Koppel.)

Mr. Rogers then dropped the mask of pretended if inquisitive politeness and sent me a savage e-mail, in which he said that he had never heard of such a disgraceful proposal. How could I, he demanded to know, propose to pay a source? Quite obviously I was morally unfit for further conversation.

Shaming the one fighting for the truth.

His indignation got the better of him. I was only making an ironic reference to Kissinger's habit of charging immense fees for his time (and at no period did I think of him as a "source").

I wrote back to Rogers, saying that he seemed to be the same man who had attended the Kissinger-Pinochet private discussion on 8 June 1976 during which Pinochet had threatened a Chilean exile then living in Washington.

On that occasion, I pointed out, the record showed that Mr. Rogers had sat in silence. It was therefore good to know what did, and what did not, touch his nerve of outrage.

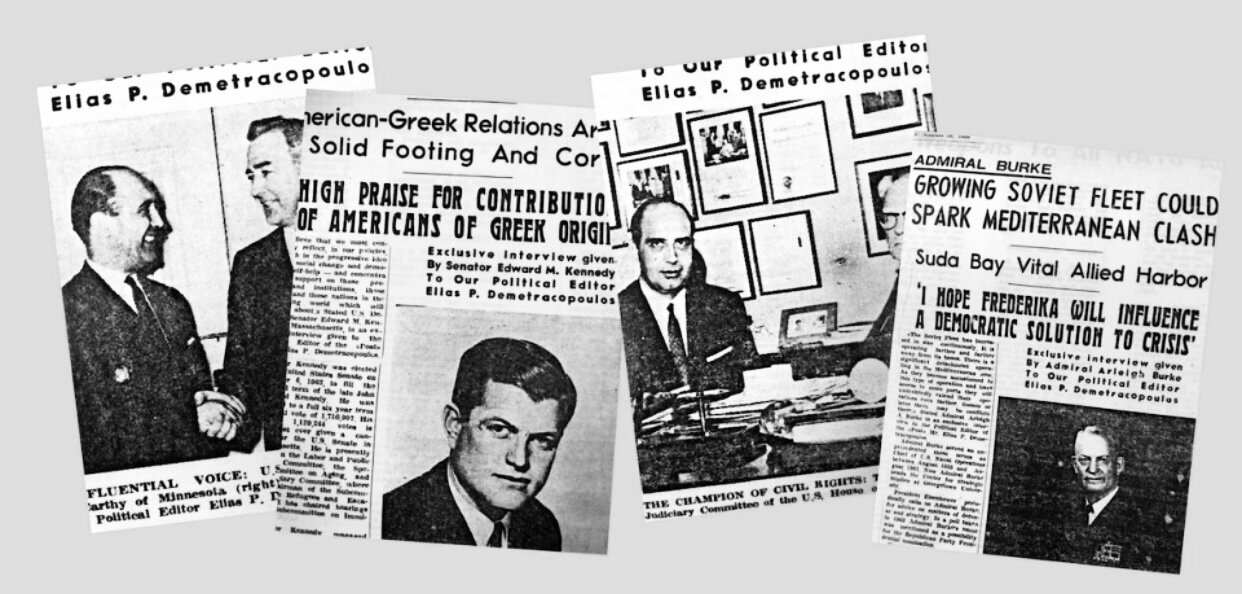

Elias Demetracopoulos

Mr. Rogers, it now turns out, also played a role in facilitating the Kissinger-Guzzetti conversations in 1976, and later in trying to put a positive shine upon them. Such men are always, it seems, with us.

The link is here.

The absurdity of the official pretense, that Elias Demetracopoulos was beneath Kissinger's notice, is even further exposed by a recently declassified letter from Kissinger to Nixon, sent on 22 March 1971. It is headed

"SECRET: The Demetracopoulos Affair."

It begins by saying to the President: “You may have heard some repercussions from the recent flap over a request by Greek 'journalist' and resistance leader, Elias Demetracopoulos, to return to Greece to see his sick father." (It's rather flattering that Kissinger should have put “journalist" in sarcastic quotes, but left the definition of resistance leader unamended.)

The letter goes on to say: Since Demetracopoulos has such a following in Congress and has an outlet in Rowland Evans [then a senior Washington columnist] I thought you might be interested in knowing that he has long been an irritant in US-Greek relations. Among his intrigues-which have included selling himself as a trusted US agent to anyone and everyone-he has touched off a record number of controversies and embarrassments between Greek and American officials. Through various journalistic enterprises, he has somehow managed to gain access to press and government circles. CIA, State, Defense and USIA have repeatedly warned officials about Demetracopoulos...