Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

In this excerpt, Hortense is made Queen of Holland and all she sees in it is increasing bondage from her husband.

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

CHAPTER VI

THE QUEEN OF HOLLAND: THE COURT OF KING LOUIS (MAY, I806----APRIL, 1807)

Prince Louis Is Called to the Throne of Holland—Last Glimpse of France—Arrival at the Hague—Public Rejoicing, Private Misery—Trip to the Rhineland—The Battle of Jena—Two More Admirers—Portrait of Talleyrand—Home-Life of the King —Domestic Peace-Treaty and Why It Was Not Signed.

SUCH moments of innocent amusement were of brief duration. Youth needs them, but as soon as I returned to my home, I found myself once more in an atmosphere sternness and severity.

My sorrows were not yet complete. A delegation headed by Admiral Ver Huell arrived from Holland, and my husband informed me one morning that the Emperor had just told him that he, Louis, was to be King of Holland.

“I do hope you will not accept the appointment," I exclaimed. As a matter of fact I expected my husband to make the same objections he had employed when it was a question of giving a throne to his son, and I thought he would refuse this crown which he did not seem anxious to obtain.

As soon as the question of his nomination came up Caroline called on us. "I attended the marriage of Prince Eugene at Munich," she said, "only on the express understanding with the Emperor that I was to have the Dutch crown.

I do not wish to remind him of his promise without your consent, but will you not allow me to do so?" Both my husband and I assured her that we should be delighted to see her receive the crown, but she did not succeed in getting it.

My fate had ordained that these royal honors were to be the bitterest of all my afflictions since they involved a separation from all that was dear to me, from all I had in the way of consolation, from my family, from my friends, from the land which I had been taught to love so dearly, at a time when I was already miserable. I admit that my husband's calm manner surprised me. I did not believe he was ambitious, yet I recognized that he was well pleased with what had occurred.

Until then every change had been a source of annoyance to him. But now he enjoyed the idea of becoming independent, of becoming his own master and, what was more, of becoming my master at the same time. No longer would any social decorum, any sense of obligation restrain him from exercising his rights over me.

Freed from the proximity of his brother he had no longer any cause to fear him. This, as I understood later, was the reason for his secret joy and the apparent resignation with which he accepted the offered throne. As for me I had no illusions as to my fate; I knew my hardships would increase.

For a moment I had the idea of flinging myself at the Emperor's feet, revealing all the torments I suffered with my husband, and begging permission not to be obliged to follow him into a foreign country where nothing would restrain those traits in his character, which I knew so well and dreaded so intensely. But when my eyes fell on my children the idea of being separated from them seemed to me the most cruel fate of all. I stifled my distress, I made up my mind to accompany these little ones and shower on their tender youth all that care of which it stood in such great need. I kept thinking of a tale which had made a deep impression on me in my own childhood of how a woman, having left her husband, returned to his house years afterwards and took the post of housekeeper, suffering rebuffs and humiliations of all kinds in order to be able to look after her dear children and live beside them.

I was convinced I was like the mother in this story, that ascending this throne was the same as entering into bondage. Thus, maternal love gave me the strength to accept my new and painful duties. Everything combined to cast a dark shroud over this rise in rank which caused me so much alarm. We were in mourning just then for the Princess of the Asturias. It was in black that I received the congratulations, which my tears might have made seem like an expression of condolence. Misfortune makes one superstitious.

My sadness in the midst of the general gloom made me still more alarmed as regards the future. Yet people thought I was happy. The Prince of Bavaria called on me at the same time as the Dutch envoys. My grief, which was apparent in spite of my efforts to conceal it, surprised him greatly and made him and the others fear that I disliked their country. The Emperor, in order to realize his plans, required his brothers to be ambitious. Of all the annoyances his family caused him he was the most prepared to pardon those which sprang from a desire for position and power, since those were the feelings he best understood.

Hence, he could not forgive me for being down-cast because I was to be made a queen. "Can it be," he said, "that you are not worthy of such a position? To assume the crown, to make your subjects happy—that is a prospect which ought to delight your heart. I have done something for you the like of which is not to be found elsewhere. The constitution makes you regent in your own right. This honor is a flattering one. Show that you deserve it."

“Ah, Sire," I exclaimed, "you can do what you please. I shall always have middle-class ideals, if that is the term to apply to love for one's country, one's friends and one's family." He laughed at my remark and cut short my farewells with my mother in order to prevent too great a display of emotion.

At one time it had been suggested that my children remain in France on account of their being the sole heirs to the throne. The Council of State had been favorable to the idea, but the Emperor, who when my husband refused to allow him to adopt our son had caused a decree to be passed by which he became the legal guardian of all boys in his family after they had reached the age of seven, was reluctant to have this law infringed on, and perhaps also wished to avoid objection from us.

Monsieur de Talleyrand, who told me the above details, was very anxious to have his brother Boson de Perigord appointed as our grand chamberlain, but my husband refused. All the younger members of the French nobility who had not yet definitely rallied to the Imperial party at court thought they could reconcile their political attitude and their ambitions by seeking to obtain appointments at the Court of Holland. Monsieur Rainulphe d'Osmond asked for the post of chamberlain, another person that of equerry, but those whom my husband referred to as "agreeables" were not the kind of persons likely to appeal to him, and he declined to consider their requests.

As I was on the point of leaving for Holland Monsieur Adrien de Montmorency informed me that Madame de Gesvres, a woman eighty years of age, had been ordered to leave Paris. I went to Saint Cloud to see the Emperor in regard to the matter. When he learned that the unfortunate woman was so advanced in years, and especially that she was the last descendant of the famous Duguesclin, not only did he allow her to remain in Paris, but he bestowed on her an income of six thousand francs.

This is an example of how severe he could be when acting on reports received through the police service and how he would palliate this severity when informed of the truth. People of high rank should at least be able to enjoy that pleasure which comes from doing good, and this is a delight of which the heart never tires. Consequently, my most agreeable occupation before my departure was I to obtain favors for people in whom I was interested.

Nominations in the tax-collecting department were the only appointments which the Emperor made directly and which could be obtained through influence. All the other posts had to be applied for through the different departmental channels. For two years I had been seeking to obtain a position in the tax-collecting department, worth twenty thousand francs a year, for the fiancé of one of Adele's cousins. The family of the girl were eagerly awaiting this appointment before concluding the arrangements for the marriage. I had already several times bored the Emperor with my petitions in regard to this matter, when one day I heard that unimportant though the post was it had been given to another candidate.

I did not dare speak to the Emperor again about it directly, but I complained to my mother saying that, having promised me a favor which would cause rejoicing in a family in which I was interested, he forgot my petition and did not even grant me this small wish. My mother reported my indignation to the Emperor, and it had the desired effect. The Emperor laughed, and that same evening sent me a note appointing my protégé receiver general of taxes in one of the principal cities in France, a position carrying with it an income of 100,000 francs.

How delighted I was at the thought of the happiness I was about to dispense. I myself bore the glad tidings to that modest household whose members a moment before might have been complaining at the harshness of Fate, and which now was safe from everything except the shock of a too sudden felicity. The marriage of Adele was another matter that was much on my mind at this time. I was as difficult to please in making my choice of a husband for her as I had been in selecting one for myself. No one seemed to measure up to my standards. It was agreed that she should join me in Holland, where I hoped to find a man worthy of her. I must do my husband the justice of saying that in spite of his usual suspiciousness of all women he never dared suspect the character of Adele. Her gentle nature, her well-balanced mind obliged him, as they did everyone else, to submit to her charm and at the same time to admire her.

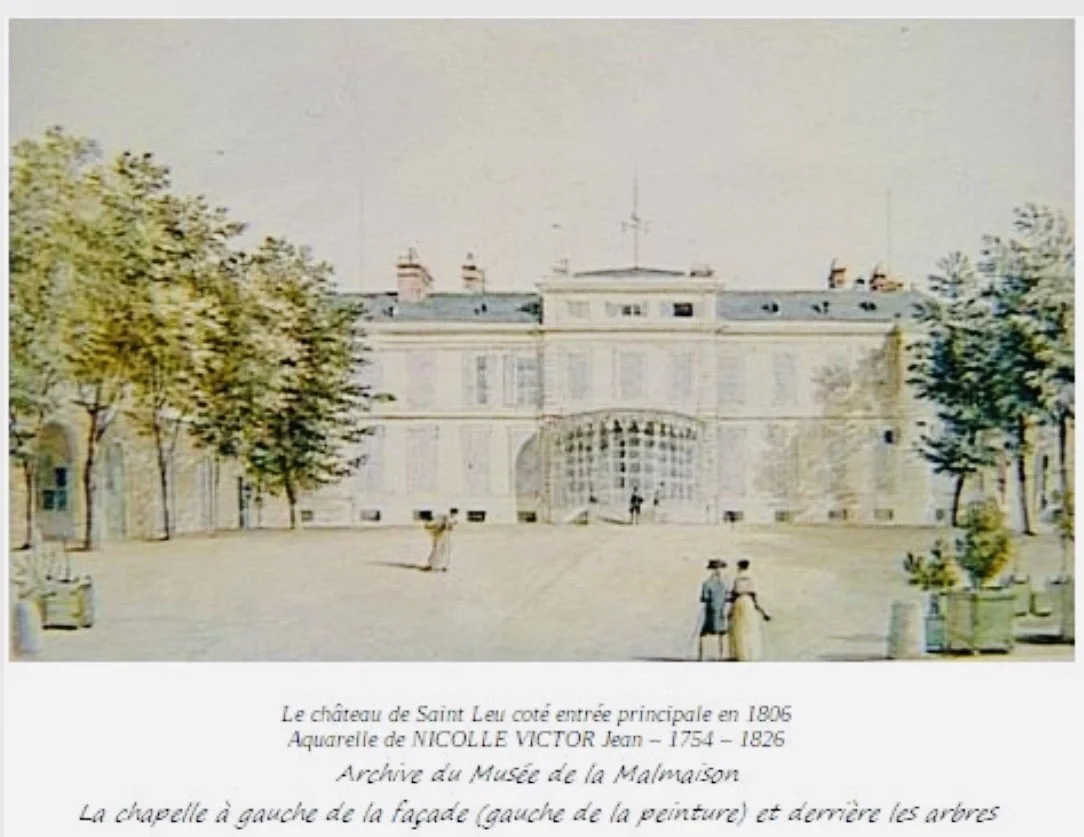

For a long while he sought to make her act as judge of our domestic difficulties. He explained to her his grievances and attempted to justify his conduct. Not being able to convince her that he was in the right, he finally ceased to honor her with his confidence. When I said good-bye to Adele the hope of seeing one another in the near future assuaged our grief. Saint-Leu had been fixed as the point from which we were to start on our journey. My husband and all my household were already there. I came back late one day from Saint Cloud where I had with so much difficulty said farewell to my mother and I stopped at Paris to make final arrangements.

The courtyard of my house was full of baggage carts and people. The first part of our baggage train was about to leave. All this bustle and the sight of the horses which were to take me away from home were painful to me. Two days more and I in turn should be saying adieu to France.

Finally, the carts started and complete silence took the place of the earlier confusion. At that moment the only servant remaining in the house informed me that a visitor was asking for me who wished to speak to me in private. It was Monsieur de Flahaut.

The fact that it was impossible for him to enter my house under normal conditions had not prevented him from casting aside all prudence in his desire to bid me good-bye.

For the first time since I knew that he was dear to me I found myself alone with him. Alarm and emotion held me spellbound. As he stepped nearer to me, I uttered a cry. "Remember," he said, "people may come in and you would be compromised."

“Ah," I replied, "I do not care what people think about me as long as I do not do any harm." Then, with the utmost simplicity, I confessed my love for him. At the same time, however, I declared that dear as he was to me virtue was still dearer, since it was virtue alone which sustained me in the midst of my husband's hideous suspicions, that it was my only true consolation, and without it I could not survive.

I told him I wished him every happiness, I assured him he would always have my friendship. I left him in a condition that cannot be expressed in words. I was proud of having such control over him, and the consoling thought came to me in the midst of the tears evoked by so sad a parting that at last the man whose admiration meant so much to me knew what was in my heart. Yet how much dearer a person becomes when he has seen us to our best advantage, when he has been able to appreciate our qualities, especially if others are blind to them and accuse us unjustly.

The original French is available below: