Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

In this excerpt, we see how an individual just so happens to appear who mirrors their target so that the individual can gain trust in order to make their destructive move aimed at controlling and harming the target later.

This trick was done to Hortense AND it was done with Napoleon. In both cases, the maneuver was successful in harming the unfortunate targets. It really was the Trojan horse Marie Louise that brought Napoleon down.

Every agent who shows up trying this with me tells me what I want to hear and they even change their look so they’ll more resemble my tastes. We see this with the last fake populist movement that I was covering. I knew it was subverted but as usual, it was even more corrupted than I had thought at first.

I have also been sent a string of “Flahauts”. Understanding this story has helped me ward off agents.

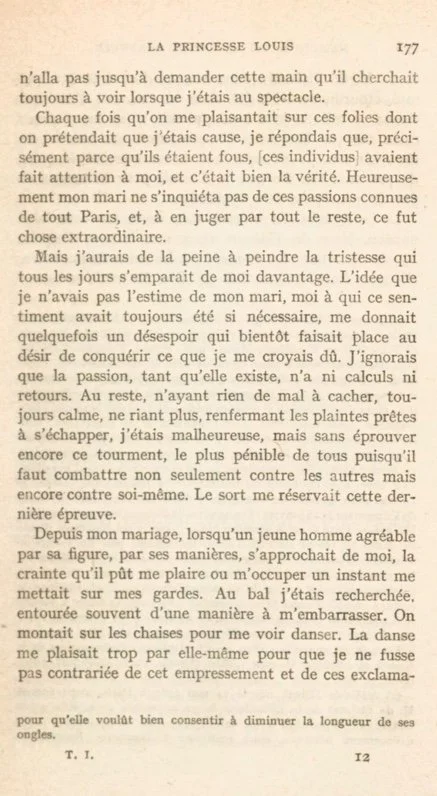

Hortense’s memoirs continues:

Since my marriage, whenever a young man appeared who was pleasing in looks or manner, the fear that I might be attracted to him, even for an instant, put me at once on my guard.

At dances I was popular and frequently to such a degree as to make it embarrassing. People would stand on chairs in order to watch me dance. I enjoyed dancing so much in itself that I could not help being annoyed by this attention.

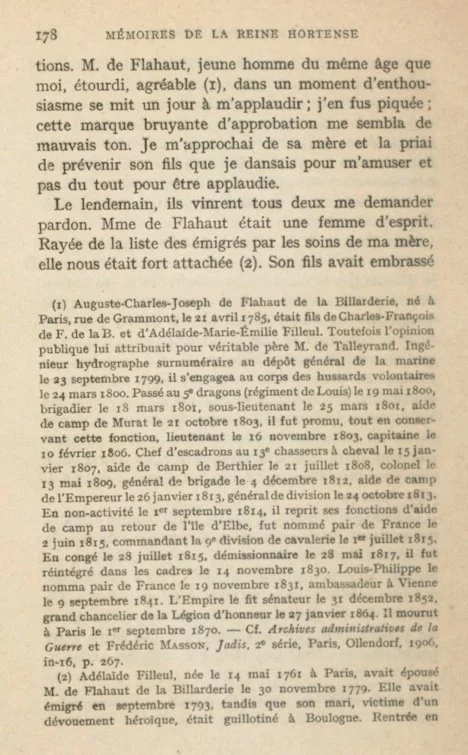

One evening, a Monsieur de Flahaut, a young man of my own age, who was agreeable and rather impulsive, did not restrain his enthusiasm and burst into applause. I was nettled by this action. This noisy mark of approval seemed to me to be in bad taste.

I stepped up to his mother and asked her to tell her son that I danced for my own amusement and not to win the applause of others. The next day they both called to apologize. Madame de Flahaut was a clever woman. My mother had been instrumental in having her name removed from the list of royalists debarred from reentering France, and she was much attached to us.

Her son had joined the army when he was fifteen. My husband had placed him in his regiment and protected him.

Later, Murat chose him as aide-de-camp. He was received in our family circle without ceremony, and his frivolous disposition, in spite of his mental gifts and good looks, had made me consider him merely as an agreeable guest and not at all a dangerous one.

He frequently came to see my husband and felt obliged to pay his respects to me before leaving the house. As I was generally busy in the morning, I often declined to receive him unless I happened to be taking my singing lesson. As we had the same teacher, we were able to sing duets.

One day, when he was announced and I thought he was still in the anteroom, I answered rather sharply, "Tell him I'm not at home." He was just behind the servant and overheard me. I was embarrassed and tried to excuse myself but could not help noticing his downcast expression.

One always feels more guilty when one causes a moment's unhappiness to a person who is generally gay. Suddenly Monsieur de Flahaut ceased to appear at our house. I thought this was due to my discourtesy. As he did not attract me (that I was quite sure of) I did not hesitate to look him up in order to destroy the unfavorable impression he might have formed of me. I met him at Caroline's and there I reproached him politely for not coming to see us.

He replied assuring me that he had called frequently but never found me in. I considered this simply an excuse and in order to convince myself of the fact I asked our doorman for the list of visitors who had left their names.

Widely believed to be Talleyrand’s natural son, Charles de Flahaut. Was he a royalist infiltrator? You will know him by his actions.

Sure enough Monsieur de Flahaut's name did appear frequently. I could not understand what this meant. A mystery haunts one’s mind till it has been solved. I wanted an explanation and finally discovered that my husband without saying a word to me had given orders that the young man was not to be admitted.

Louis' jealousy in this instance appeared stranger to me than ever. I thought to myself, "Why should he worry about a young man who does not please me at all, whom I consider fickle, to whom I even behave rudely? But the young man will think me insincere or perhaps coquettish, for I invite him to call and yet refuse him admittance."

It is disagreeable to give people a wrong impression of yourself. That was my reason for continuing to think of this incident. At last, one night at a dance while supper was being served Monsieur de Flahaut complained to me that he had been turned away from my door while other visitors were being admitted. He might have been spared this mortification in view of the long-standing attachment which existed between our two families.

I was touched and embarrassed. I tried to console him saying, "It was not my fault, but I beg of you do not call again." Instantly I realized the mistake I had made, for with a glance that surprised me he exclaimed that he was delighted to learn that it was not I who had refused him admission, and he added with remarkable tactfulness "You will never see me again, for the idea that an action of mine should cause you inconvenience would be more than I could bear."

The impression his words produced on me may be left to the imagination. Here was a man who was aware of my husband's jealousy. I had made the mistake of revealing it to him. On the other hand, a young madcap, to whom I ought to pay no attention, showed that he sympathized with me sufficiently to promise to avoid me, to respect my peace of mind.

This was love as I understood the meaning of the word. I was overcome with surprise at being, for the first time in my life, dissatisfied with my own conduct and at finding in a young man of the world a heart whose purity of sentiment was equal to my lofty standards.

In spite of my efforts my thoughts kept returning often to Monsieur de Flahaut. My brother asked us to a dinner at his country place called La Jonchere. The party was a large one. Among the guests was a young Polish countess who was leaving France the next day. Her sadness was apparent to all observers; she loved Monsieur de Flahaut and was about to bid him farewell. She seemed overcome with grief. He too had tears in his eyes and could not conceal his feelings. I was touched by the sight. I said to myself, "He is indeed capable of loving someone. He is suffering; he interests me. I made a mistake when I judged him superficial.

He has shown his friendship toward me and he shall have mine he deserves it and I can give it the more readily since, being in love with another woman, he is harmless to me."

During one of the trips of the Emperor to Boulogne, Caroline came to see me about sending him good wishes for his birthday. Since my letter at the time of his marriage I had never written to him, and together we composed two letters practically alike. The answer to Caroline was merely dictated to a secretary and signed by the Emperor. The answer to me was charming and entirely in the Emperor's own handwriting. Caroline, vexed at the difference, complained of being slighted.

She did not actually declare it was my fault, but quite naturally a little jealousy was mixed with her annoyance.

Have you noticed that throughout the memoirs, we see Napoleon complaining that Hortense doesn’t love him or pay him enough attention and that he doesn’t speak in this manner about anyone else?

My mother went to take the waters at Aix-la-Chapelle, The Emperor was to join her there after his trip to Boulogne, and they were to visit Belgium and the Rhineland. At Aix-la-Chapelle mother made herself as popular as she did everywhere she went. On his arrival, the Emperor was received with great enthusiasm.

People were grateful to him for having brought back the relics which since the days of Charlemagne had formed the glory of the city. The canons of the cathedral and the municipal authorities felt that the way they could best show their gratitude to the man whom they looked upon as a new Charlemagne was to present him with an object which had belonged to his great predecessor.

They selected a charm which Charlemagne always wore when going into battle and which had been found still attached to his collar when his tomb was opened in the year ___ My mother requested that in addition to the charm they add a bit of the bone from Charlemagne's arm which was preserved in a shrine, a little statue of the Virgin supposed to have been carved by Saint Luke and a bit of the four great relics (a linen robe of the Virgin, the swaddling clothes of the infant Christ, the cloth that had enveloped Christ on the Cross and the handkerchief in which had been wrapped the head of John the Baptist).

I still have all these objects. During their stay in Belgium, the Emperor and the Empress received the visits of all the princes and princesses of the small German states who wished to attach themselves to the destinies of the French government.

They felt that the title of Emperor conferred more stability on the ruler of the French nation. They also found it more natural, more in keeping with their traditions, to pay homage to an Emperor, to be dependent on him, to look towards him for defense, to entrust their interests to a sovereign bearing that title rather than to a ruler holding office for a limited period of years, a successor to those various governments which had followed one another so rapidly and whose authority was equally precarious. The Emperor met these princes at Mayence, reviewed their troops and held maneuvers of his own forces, which were under the command of Eugene. The public surmised, therefore, that an alliance was about to take place between my brother and one of those ruling royal families of Germany who had hastened to present their respects to the Emperor all the more eagerly as the power of the Empire increased, even in the eyes of its enemies.

At this time my husband went to Plombieres for his health and from there to Turin to preside over the deliberations of the electoral college. As I was about to have my second child, I could not accompany him and remained in Paris. My life would have been calm enough had it not been disturbed by that emotion which was already beginning to agitate my mind and heart. I did not by any means realize what was the matter.

When people spoke to me I sought to bring up the subject of the feelings of those who are in love ; I trembled at the thought that I might experience those feelings, which I dreaded, and if the person I was talking with described love as a state of passion and frenzy, I breathed more freely, saying to myself,

“What a relief, then I cannot be in love." I went daily to the Bois de Boulogne accompanied by Madame de Boubers, my son and, frequently, by Monsieur Lavallette. Monsieur de Flahaut rode there regularly.

Sometimes, we would even take walks with him. I no longer asked him to the house, but he always managed to be where I was and never missed an opportunity of declaring his sentiments toward me. When he did so my poor opinion of him revived.

I believed it was not possible to love more than once. He seemed to treat too lightly that young Polish woman whose grief had touched me, and this idea put me on my guard with him. If he spoke to me of her with respect and emotion I would weaken and would treat him kindly ; if, however, his conversation was about his affection for me, which he declared was of long standing and which his liaison with the Polish woman had not been able to destroy, I would repulse his advances.

At such times I would again consider him as one of those fickle men who only seek to please women and obtain their favors. I saw Monsieur de Flahaut almost every day. The moment I caught sight of his gray horse in the distance my heart began to beat. And yet I declined to admit I was in love. When he asked me where I should be on the morrow, I answered I had no idea.

Any other reply would have seemed to me too much like giving him an appointment. In spite of this I saw him everywhere I went. Princess Caroline had a handsome estate at Neuilly. She often invited me there.

There were boating parties and dances in the evening. One day, apparently much distressed, she said to me, "Just see what a gloomy mood that young Monsieur de Flahaut is in. I have tried to get him to dance, and he declines obstinately to do so.

I wish you would try and see if you can't persuade him." I called Monsieur de Flahaut over to me. He informed me how, that morning at lunch, in front of the servants, Caroline had teased him about his assiduous presence wherever I happened to be. He had answered sharply, but the thought that such remarks might hurt my reputation and expose me to malicious gossip was profoundly disagreeable to him.

Caroline.

I was touched by his concern. I told him to go and dance, and he obeyed me. Caroline, who wished to see whether I had more influence than she over a young man attached to her household—Monsieur de Flahaut was at that time one of General Murat's aides-de-camp—was convinced by his actions that a single word from me carried more weight with him than all her entreaties during an entire evening. From then on, she neglected no means for regaining an influence she should never have lost.

It was well known that Caroline was jealous of Hortense and that Hortense was desperately lonely and unhappy with Louis.

She appeared to sympathize with him, sought to cure him of an attachment which could only result in making him unhappy. She described me as a person who was kind and gentle but too aloof ever to be moved by any tender sentiment. She told him I was sufficiently vain to wish to have numerous admirers in attendance whom I soon tired of and, moreover, that I was tortured to such an extent by my husband's jealousy it was a sin for anyone to think of adding to my troubles.

Never had a word from me allowed Monsieur de Flahaut to think I was the least interested in him. But the eagerness that was shown to cure him of his infatuation was so great that for a time he avoided me and disappeared entirely from sight. I was at first surprised at this. But my feelings of surprise soon changed to consternation when for the first time to my knowledge I became aware of what emotions were agitating my heart.

This discovery terrified me. The intensity of my feelings, the manner in which they dominated my thoughts, seemed proof to me that they could not be wholly evil. Yet it was essential I stifle them. I summoned up all my will-power to do so.

Adele returned just at this time from a short trip to Switzerland with her sister. I threw myself into her arms, burst into tears and told her my troubles. She sympathized with me. It was agreed between us that we should seek to discover all the possible flaws and defects in the character of this man whom I ought never to have noticed.

Taking as an excuse a new song he was sending me, Monsieur de Flahaut wrote me a letter full of delicacy of feeling and expression. I did not reply but tore it up after having shown it to Adele. As the letter seemed to us excellently written, we decided, in accordance with our plan, that it was not composed by him but by his mother.

I’ve also translated a letter by Josephine where it’s clear Flahaut’s mother is trying to seduce Josephine into falling even more into debt.

Only a woman could have expressed her-self in such a manner. Presumably I was considered to be like the heroine of some novel whom it was easy to lead astray. But all these criticisms were in vain. I was suffering. My heart was heavy. I prayed fervently. I was wounded, but I hoped to be cured. I sought to understand my feelings in order to combat them, to find a remedy as powerful as the disease.

One day I felt I was on the road to recovery. I had not been at Neuilly for a long time. I went there. Caroline was on the island. I waited in the moonlight for her to come back. She returned with her arm in that of Monsieur de Flahaut. This sight caused all my blood to rush to my heart.

She too appeared so confused at seeing me that I was astonished at her emotion. As for Monsieur de Flahaut, the more anxious he seemed to speak to me the more I avoided him. But the difficulty I felt in doing so, the intensity of my emotion was so great as to make me realize the truth. I was in love.

This knowledge completed my despair. When I left Neuilly, I was greatly upset. On returning home instead of retiring to rest I gave way to my gloomy thoughts. I regretted that my husband was not at hand, that he had not returned as I had asked him to when I first felt myself in danger.

The original French is available below: