Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

In this excerpt, Hortense keeps getting enlisted into working for Napoleon as a reader but she is not very good at it. She also shows that Napoleon particularly respected scientists and he was very interested hearing their honest opinions.

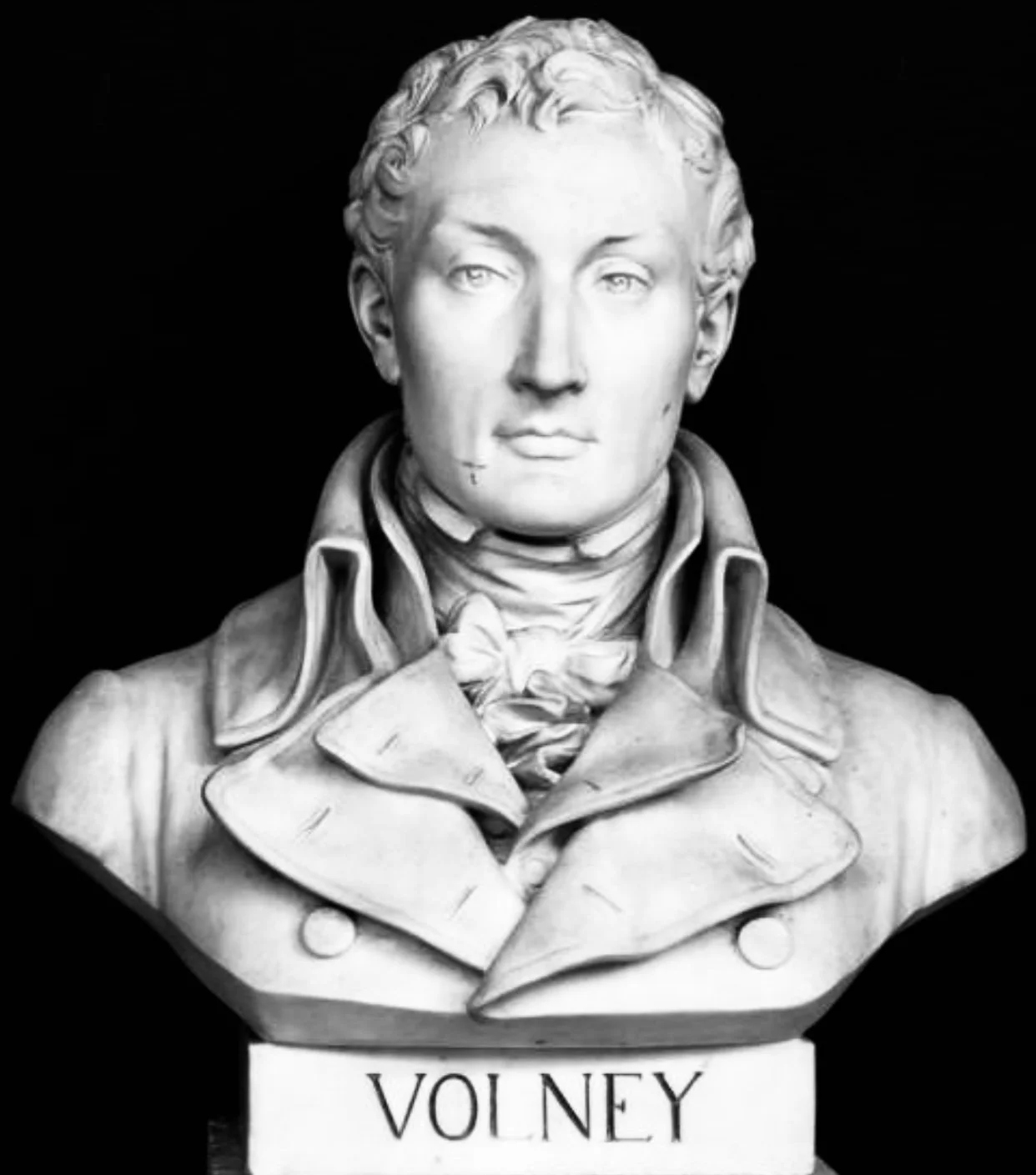

I learned later that his [Volney’s] fidelity to republicanism caused him to see less of us during the Empire. The Emperor never resented this. He respected all opinions as long as they were honest and sincere, and I recall having seen him very much upset in 1812 or 1813 on hearing of an accident that had happened to Volney.

The scientist had been walking along quietly when a bull suddenly charged him and tossed him some distance into a field. I also saw the Emperor distressed by the news that Monsieur de Lafayette (who like Volney avoided us) had broken his leg on the ice as he was coming out from a ball.

The Consul was always anxious to meet and surround himself with eminent men of all kinds. I have never understood why people said he was jealous of others. On the contrary I always felt that he sought to honor in every respect those whose achievements added to the glory of France.

The only thing he would not consent to share was his political authority. He considered that this was indispensable to insure the success of his vast plans and the best interests of his country. Therefore, he would not share it or allow it to be weakened.

Moreover, the enthusiasm of the crowd, the esteem and consideration shown him by everyone he encountered proved his superiority. He seemed born to command other men.

I have always seen him the same, as General, Consul and Emperor. His generals never spoke to him familiarly. Neither Lannes, Berthier, Augereau, nor Lefebvre ever sat down in his presence. He impressed them even more than he did others with a sense of his personal preeminence of which they were all conscious.

A difference in rank has always been considered respectfully in France. I have seen Lannes, Bessieres, Murat furiously angry, jealous of each other and talking of leaving the Consul's service because, according to them, he had treated them unfairly in the way of promotion.

Frequently I managed to reconcile them, but whether or not I did so the moment General Bonaparte appeared no one said another word. Sometimes they would have a sullen air if their pride had been too deeply wounded.

The General, always aware of what was going on, guessed their thoughts and by an abrupt phrase or a gentle pull of the ear made the insurgent as meek as he had just been the contrary.

Scientists seemed more at their ease with the Consul, for he always allowed them to speak their minds freely. But they remained standing in front of him, following his remarks with avidity and a sort of admiration. I am sure that the authority the Emperor wielded was due to the fact that all those who spoke to him felt he was superior to anyone else in his intelligence and that since it is necessary to have a ruler no one was better qualified than he.

The Consul had so great a respect for all forms of learning that if a distinguished man did not come to see him he would find time, in spite of his many duties, to visit the scholar.

One day he went out for a drive with my mother and myself. We went to the Jardin des Plantes to call on Daubenton, the naturalist, who lived in a little pavilion giving on the garden. He seemed very, very old as he sat in a large armchair, but in spite of his advanced years spoke with great animation. The General asked him many questions about Buffon. I have always been sorry I did not keep a letter the General received from Beaumarchais after his return from Italy. I might have done so easily enough. The letter was so flattering and so well written that he read it aloud to my mother and me.

At that time he was receiving so much praise, including expressions of such a fulsome variety, that I could not help noticing what was said with wit and moderation. The compliments Beaumarchais paid him struck me as being in the best of taste, but that letter like so many others was burned.

In the days of the Republic, when polite social life was completely destroyed, the republicans wished to have the upper classes adopt the manners and habits of the mob. Under the Consulate, on the other hand, the Consul in bringing the different strata of society together, sought to introduce into what had formerly been exclusive circles people of worth and distinction without regard for their origin.

So deeply are aristocratic traditions rooted in France among all classes that the enterprise was far from easy. Nevertheless, he attempted it.

He went so far as to invite to dinner at Malmaison some famous actors. I saw there, one after another, Talma, Mademoiselle Raucourt, Mademoiselle Contat, Mademoiselle Fleury, all distinguished artists and possessing excellent manners. But people took offense, and so strong is the force of prejudice it was quite as much the newly enriched commoners who objected as the old nobility.

On the other hand, one day at the Tuileries the Consul invited to his table two old soldiers, one of whom was over a hundred years of age. I remember it was a dinner attended by the members of the first mission from Russia. One of the young princes attached to the mission, who sat beside me, told me that on their way through Germany everyone tried to frighten them by speaking of their foolhardiness in venturing into France where massacres took place all the time.

Although he had not believed these tales, he was surprised to find out on arriving that all one heard talked about here were balls and receptions.

One day an old woman called at Malmaison who seemed to be a hundred years old. She was dressed in the fashion of the days of Louis XVI, with a little black tulle bonnet shaped like a raven's bill, semi hoopskirts and a brocaded gown set off with pockets. Only the stage had kept such costumes for those who played the parts of old women, and no one would ever have suspected that the person dressed in this fashion was the beautiful and famous actress Mademoiselle Chiron, who had once enchanted all of France.

It was she who was the first to discard the habit of wearing dresses that were merely fashionable in favor of those suitable for the different heroines she portrayed. "I wished to see a hero before I died," she said to my mother, "and I thought, madame, you would not refuse me this pleasure."

Indeed, my mother was very kind to her and invited her to spend part of the day at Malmaison while waiting for the Consul to appear. When he did arrive, she looked at him attentively, and if by accident anyone interfered with her view of the First Consul in the drawing room, she would request the person not to conceal him from her during the few moments she had an opportunity of seeing him.

The Consul was most gracious to her and among other things said, "I have heard so much of your admirable talent I greatly regret never having witnessed one of your performances."

“And I," she replied promptly, "am delighted you never did." Everyone was astonished, and she went on, "Had you done so you would now be an old man, First Consul, and France needs you to remain young." Mademoiselle Chiron died some time after this visit, having received from the Consul the assistance she needed badly.

Sometimes in the evening when the Consul had invited no one to Malmaison he would send for a new book and ask me to read aloud. I was so embarrassed by the idea of doing so in front of him and all his staff that I could not tell one word from another. Then he would say, "Didn't Madame Campan teach you to read?" A remark which redoubled my embarrassment. One day he brought out "Ayala," which had just appeared.

I remember it as being a very difficult ordeal. The names of trees, places and animals which abounded in this volume were new to me, and I mispronounced them as though I were doing it on purpose. It was a great trial. If I had only dared, I should have pronounced them haphazard and no one would have noticed it, but I stopped each time and seemed to be spelling them out.

I was so evidently ill at ease that after a few pages the Consul stopped me and never again tried to make me read romantic literature. But another difficulty lay before me. One day he asked me to read him a general report from his minister of finance, a report which was to be presented to the legislative bodies.

It was so full of piled up figures that I had as much trouble as with "Atala." I frequently took one column for another and substituted hundreds of millions for hundreds of thousands or billions of francs.

The Emperor seemed to have all this clearly in his mind, for he never failed to correct me, rectifying my errors, and he always ended by saying, "Didn't Madame Campan teach you arithmetic?" I must say in defense both of Madame Campan and myself that never did columns of figures seem so appalling.

After dinner the Consul would take my mother's arm and stroll about with her for a long time. I would remain alone surrounded by his entire staff. Although at first I was embarrassed I soon became accustomed to the situation. I felt I must conquer a shyness which might make these young men treat me in a too familiar manner and consequently either ignore me completely, or be too conscious of the embarrassment their presence caused me.

I therefore adopted toward them the attitude of a woman in her own home, who sets the tone of the conversation. I must say that these soldiers, whose life under canvas had kept them away from drawing-rooms, never used a word or an expression that might have shocked me. It is true I chose as topic for our conversation the subject most likely to appeal to them. I questioned them regarding their campaigns in Italy and Egypt. I asked them to tell me the story of their exploits. I praised them and criticized them and I went as far as to give them advice regarding the things in which they were most interested.

I pictured to them what I imagined to be domestic bliss, the only reward they should seek after having won so much glory. I gained their confidence so completely that they consulted me regarding all the offers of marriage they received.

One of them wished me to judge the merits of his fiancée. Another declared he would marry only a girl I chose for him, who shared my views on life, and he asked me to find him someone of this description.

I enjoyed their esteem, affection and regard. As had been the case at Saint-Germain I felt proud of arousing such sentiments, the more so as they appeared to be based entirely on my personal character.

Perhaps this idea made me a little vain, but it strengthened me in my opinions and in the desire to deserve this consideration that was offered me so freely. The officers whose duties brought them oftenest to Maimaison were the Generals Bessieres, Lannes, Clarke, Junot, Murat and the aides-de-camp Le Marois, Caulaincourt, Rapp, Caffarelli, Duroc, Savary, Lauriston, Lacuée, Lebrun, Lefebvre and Bourrienne, the Consul's private secretary.

My brother, major in the Chasseurs de la Garde, was a frequent visitor. Louis Bonaparte, who commanded a regiment of dragoons," did not come so often.

Lavallette was special envoy at Dresden. His wife had reluctantly decided to live with him. For an instant she had hoped to have the marriage annulled. On the return of the expedition from Egypt she had explained her feelings to General Bonaparte and at the same time told him she cared for his brother Louis. The latter replied that he thought my cousin a kind, good woman, but even if she were free, he would not marry her, because she had changed too much in looks since having had the smallpox.

My mother conveyed this message to my cousin, who was indignant. On the other hand, the attentions of her husband, the care he took of her, and his kindness to her gradually on her heart and aroused a warm affection toward the person she had avoided.

Since then a lasting union has been the result of this change of heart. Louis' attitude toward my cousin had prejudiced me against him. The fact of our being in a sense related to one another caused me to look on him as a brother, and when occasion offered, I sometimes jested at his expense.

It had never entered my mind that he could become my husband, that he could have the least affection for me. But when he came to say good-bye before leaving for Prussia he asked permission to kiss me, did so with such evident emotion, and went out of the room so hurriedly that I remained standing motionless.

A kind of terror seized me when I conceived the idea, he might nourish too warm a sentiment for me. Of all the young men I came in contact with, only one, Colonel Duroc, dared propose.

Recalling the fact that the Consul had planned to marry him to his sister, he thought that my stepfather would not oppose a match between us. I had noticed that he was more embarrassed than the others in speaking to me, that he called more frequently at Malmaison, but he had never said a word as to what was in his mind.

Murat wormed the secret out of him and took it into his head to see that this match took place. "The young lady is romantically inclined," he declared. "One must sigh for some time before hoping to please her. Meanwhile you should declare your sentiments and inform her she is the object of your affections."

As a result of this advice, one day when I returned to the drawing-room to look for a book I had forgotten Duroc came up and timidly returned the volume. Ongoing up to my room I opened the book and found a letter. What should I do? To read it seemed to be committing a sin. I went back downstairs to return it to Duroc, but he was no longer there.

The Consul had sent him away on a mission. It was only at the moment of his departure that he had dared to declare himself. I put the letter in my writing table, which as usual I did not lock, and left my room. As chance would have it at dinner time the Consul, who enjoyed teasing me, came into the drawing-room with my mother and finding me there already said to me, “We have just been to your room. We have ransacked all your papers and read all your love letters. What tender missives you receive.”

I blushed, I stammered, I forgot the joke was not a new one. I felt guilty, and the idea was enough to make me look like a criminal. Uncertain what reply to make left the room hurriedly and rushed to my writing desk.

The letter was still unopened. I went downstairs again more calmly. But my emotion had not escaped the attention of my mother and the Consul. When I came in they said to me in surprise, "Can it really be true? Have you really secrets? You hurried off very suddenly."

Fortunately, the serving of dinner put an end to my predicament. The same evening, I told mother everything. Duroc had left a messenger with Murat to bring him word of my answer. I told Caroline that I would never make a decision without knowing my mother's opinion of the matter and I begged her to return the famous letter to the sender.

“I do not know," I added, "what fate holds in store for me, but I should not want to be obliged to admit I read a love letter from anyone else than the man who was to be my husband." I admit that before giving it back I was strongly tempted to try to read it without undoing the envelop, just to see how a man proposed, but I resisted the impulse and feel I had considerable merit in doing so. Duroc, although not the man my imagination conjured up as the being worthy to receive all my love, was not displeasing to me. I recognized the fact he had numerous qualities.

The great respect he had for me caused me to believe in the sincerity of his feelings. Frequently, nevertheless, when I was listening to him, I said to myself, "This is not yet the man."

Perhaps after all I should have been willing to marry him had it not been for my mother's formal opposition to the match. The Consul saw no objection, but she took the contrary view. Brought up according to the ideas that prevailed among the aristocracy, she considered it a mésalliance to marry someone not a member of the nobility.

She concealed her prejudices by being equally gracious to all those with whom she came in contact. They did not influence in any way her kindness, which was the same for all, but she considered that nothing was good enough for her daughter. Although Duroc was a gentleman she demanded higher rank either in him or in his family.

“I cannot imagine hearing you spoken of as Madame Duroc," she said to me. "Are you in love with him? I should be so sorry if you were." I reassured my mother. I told her my heart was untouched, my life was happy, I did not care to consider change of any kind. I felt sincerely uneasy over what to others might have appeared a mere incident of no importance. The idea that I was hurting someone was unbearable.

I took seriously everything that had to do with affairs of the heart. I could not laugh at a thing that sprang from that source.

Bourrienne, the Consul's private secretary, was a man of a certain age. He was very plain, witty but only in a satiric manner, and more to be feared in a drawing-room on account of his malicious way of stating a case than on account of his official position.

Of a sudden he began to look glum, speak little, read nothing but Young's "Night Thoughts" and in the evenings go alone into the woods. People would encounter him leaning against a tree and weeping.

Even the Consul noticed his condition. The advice of Doctor Corvisart was asked, but he admitted he was unable to understand it. General Bessieres offered the unkind suggestion that only two things could produce such an effect on Bourrienne, either a financial catastrophe or an unhappy love affair.

There is money for wall to wall agents on the internet but there’s no money for a new roof at the Malmaison museum?

This threw a light on the matter. Everyone at Malmaison was convinced Bourrienne was consumed with passion for me. It was considered a case of insanity, but so serious that no one dared make fun of it openly. My mother spoke to me about it.

The idea had never entered my head. I watched for signs that would justify these rumors and speedily discovered them. No sooner had I become aware of the harm I had done unconsciously than I resolved to remedy it.

How could this be accomplished? Youth is prepared to undertake anything. Its innocence acts as a stimulus it deserves to achieve its purpose because it makes the attempt so straightforwardly and so bravely. I sought to see more of Bourrienne, to whom before I had scarcely paid any attention. It was difficult to have a conversation with him as he purposely avoided me. Finally, the occasion presented itself. I began by inquiring about his health. "You should take care of yourself," I told him, "for the sake of your wife and children. Have you consulted your doctor?"

"He can do nothing for me."

"Then perhaps your friends can help you. If you are suffering from some illness that is not physical but moral, you should seek help from your wife."

“She does not know what ails me. No one suspects it." "What, do you mean to say you are suffering from a sorrow that no one shares with you and that you are not strong enough to overcome?"

“That surprises you, does it, mademoiselle? But what would your feelings be if you loved deeply a person your mother forbade you to marry?"

"If the person loved me, even my suffering would be dear to me. Perhaps I should not seek to hide my feelings. But I should be ashamed of a grief that I alone felt, that distressed my friends, that prevented me from carrying out my duties properly. I should summon up my courage and conquer it."

Bourrienne gave me a long look and took my hand. "You have cured me," he said. "I thank you. You have done more for me than you can realize." From that day on he resumed his customary manner, and not a word or a look indicated that I meant anything in his life. I was delighted with this cure. I was astonished to have inspired a strong affection.

Always behaving naturally, without any attempt at coquetry I wished to be liked but made no attempt to please. While my friendly attitude toward everyone about me was doubtless prompted by a desire to be praised, with it was mingled a hope that this praise might come to the ears of the man whom Heaven had chosen for my life's companion.

“He does not know me," I said to myself, "but he will know that others care for me and perhaps that will make him love me the more."

My social life did not cause me to forget my former companions. I often went to see them at Saint Germain and also visited my grandfather, who had retired to that town. He died there at the age of about eighty-seven, surrounded by our respect and tender affection and bearing with him all our just regrets.

My ability to support all of life's vicissitudes is principally due to the fact that my imagination magnifies coming misfortunes which when they arrive appear less terrifying than the picture I conjure up in advance. Hence, I find myself with more than enough courage to face all such perils and afflictions as may befall me. I recall one occasion when a rebuke from the Consul failed to affect me at all.

My room in the Tuileries was at the end facing the garden. A little chapel at the corner served me as a work room. It was very small, barely large enough to hold two people. At the time, I was copying in oil a portrait of my brother by Gros, and all my papers and drawings were on the floor against the wall. As it was very cold in this room, a pipe for heating the place, which one could open or shut at will, had just been installed. When we left for Malmaison I had forgotten to shut it.

The next morning General Clarke came to me in consternation. "Do you know the misfortune that has taken place?" I began to tremble and grew pale as my thoughts flew to my brother, who had just rejoined his regiment.

“Tell me what has happened," I said to the General, scarcely able to breathe. "All your drawings have been burned," he replied. "All your paintings have been blackened and are ruined. There was a fire last night in your little study."

As he spoke, he watched me closely to see what effect his words would have. I felt as though he had told me a piece of good news. My heart resumed its normal beat, and laughing I answered, "How delighted I am and how you frightened me!" At that moment the Consul came into the drawing-room and said with a very stern air, "How did it happen you left papers beside a chimney? A fire broke out last night, and if a sentinel had not noticed it you would be responsible for the destruction of the Tuileries. The entire palace might have been reduced to ashes."

I listened to him with a smile. I could not manage to look distressed. The more he noticed my attitude the more angry he became as he expatiated on the disasters of which I might have been the cause. But I felt so happy at having escaped a danger which involved my affections and which General Clarke's manner had caused me to fear, everything which proved my imagination had been mistaken seemed so agreeable to me, that my step-father's reproofs produced no effect on me.

About this time Louis I of Etruria and his Queen passed through Paris on the way to Tuscany, whose crown the Consul had just bestowed upon him.

It was the first time the Consul had created a kingdom and Louis was the first Bourbon to appear in France since the Revolution. Orders, necessary in those days, had been given that the King and Queen were to be well and politely treated everywhere. They did not attract any particular attention. Only at Bordeaux did the crowd behave disrespectfully. The sovereigns were attending a performance at the theater, and an actor recited verses written in honor of the Queen by someone who had never seen her.

The author praised her beauty, at which the audience laughed so loudly that those who were with the King and Queen were much embarrassed, for although she was young, kind and gentle the Queen was exceedingly homely.

I have frequently thought of this incident in order to estimate official compliments at their just value. The King was tall with a good figure. Drooping cheeks and thick lips made his face expressionless. He was subject to epileptic fits.

He and his wife often came to Malmaison. The first day the Consul paid no attention to them; he had too much to do elsewhere. My mother was ill, and it was therefore I who was obliged to entertain them. They were not difficult to keep amused. Walks, music, prisoner's base, parlor games—everything delighted them.

In fact, when at length the Consul wished to instruct Louis in the arts of statecraft, he found him so absent minded that he accused me jokingly of having made our guest forget his royal rank.

Before our visitors left, the Consul had Berthier and Talleyrand give two receptions for them, which filled them with astonishment, particularly on account of the contrast formed by the brilliance of French society and the dullness of the Spanish court.

One day my mother introduced me to a lady who had come over from England and only once visited Malmaison. It was the Duchesse de Guiche. She did not see the Consul. If, as I have heard since, she had hoped to find in Napoleon another Monk her trip was not a success. I was too young to gather any exact details regarding the matter so I will not attempt to give any. All I know is that the royalists hoped that France, which was beginning to feel the need of permanent government, would be inclined to forget the past and call the Bourbon family back to power.

The feeling that a government only temporarily in office was not sufficiently stable was shared by men of all classes. The conspirators who had attempted to slay the Consul, with whose life the future of France seemed interwoven, had aroused such hatred that even those in favor of a new republic believed it was necessary to strengthen the powers of the Consul of such a republic, in order to prevent the enemies of the Revolution from being able constantly to endanger the results which it had cost so much to secure.

Those in favor of a monarchy demanded also that it be invested with such guarantees as would insure its stability. They considered that the talents of the Consul made him the only one able to achieve this continuity and ward off reactionary movements which were always to be avoided.

The higher aristocracy, many of whose members lived abroad, regretted its lost privileges and realized that only by a return of the Bourbons would it be possible to regain them, but it had no hope of this return taking place.

One day the Consul received a very cleverly drafted genealogical chart showing his descent from Louis XIV in the direct line. The person who in order to please all factions had imagined this hoax sought to prove that the Man in the Iron Mask was one of the sons of Louis XIII and Anne of Austria and that Louis XIV was only a second son whose father moreover was the Cardinal Richelieu.

The Man in the Iron Mask, according to the genealogist, having been sent to the Island of Saint Margaret, married there the daughter of one of the local nobles. His son had taken the name Bonaparte and had established himself in Corsica. Consequently, the Consul was the legitimate heir to the French throne. The Consul was much amused at this fairy-tale and laughed about it with us. He was always far prouder of his personal ability than of any illustrious ancestor he might have had or who might be attributed to him.

The love of his fellow countrymen was the best of his claims to office. In our drawing-room there was never a word spoken about political matters. The only one that interested us was the signing of a peace treaty, and we were the last to be informed even about that.

When the peace with Vendée was concluded the chiefs of the insurgents who came to Malmaison received a warm welcome from the Consul. He appeared to hold them in high esteem. I frequently have heard him praise them for defending their cause so perseveringly and blame the Bourbons for not having supported such a valiant resistance.

Once, after the Empire had been proclaimed, I heard him say, "I do not know what I should have been able to do if the Bourbons had put themselves at the head of the Vendeans."

The Consul's aide-de-camp Colonel Lauriston was sent to England. He was received in triumph, and his carriage was dragged about by the crowd through the streets of London. All of France also felt enthusiastic over the reconciliation of the two great countries which for so long had been enemies.

The Consul himself, who so seldom expressed his satisfaction about anything, showed his pleasure on this occasion. He hastened to announce the news to us and immediately ordered the cannon to be fired as sign of rejoicing. It was the only time I ever knew him to inform anyone, especially any woman, regarding a political event.

I do not know whether he had opened the dispatches addressed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, or if he had received the news directly, but Monsieur de Talleyrand appeared at dinner in a very bad humor, quite put out, in fact, as someone would be whose vanity had been deprived of an occasion to score a hit. As a matter of fact it was distinctly odd for the Minister of Foreign Affairs to learn that peace had been signed by the firing of the guns at the Hotel des Invalides. To console him for this little mishap. the Consul smilingly paid him special attention.

The original French is available below:

Contempt for the laws, and the disturbance of public order, are the results of weakness and wavering in princes.