Let’s have another look at Hortense’s Memoirs. If you want to read the book it is available for free at the side bar in English and French. Use the widget on the sidebar to translate the text below into pretty much any language.

In this excerpt, Hortense finds popularity at her school and her mother Josephine tells her of a prediction she received in Martinique that she would be “more than a Queen”.

On the contrary he [Napoleon] had suffered by it [the Reign of Terror] His family was an old one, honorably known in Corsica. In every respect the marriage was suitable. I accepted these arguments.

My interest in the success of my brother and the knowledge that my stepfather had had no share in the crimes which had led my father to the scaffold caused me to consider the marriage more favorably, until the moment of my mother's departure for Italy renewed my grief.

My first cousin Emilie de Beauharnais whom mother had taken care of after my uncle François's departure from France, was sent to school with me, and Jerome Bonaparte, the General's young brother, was sent to the same school as Eugene.

Having done this mother left to rejoin her husband. A short time passed, and the newspapers were filled with accounts of my stepfather's victories. Every day Madame Campan would try to read me the descriptions of them, but I refused to listen and left the room. Then she would send for me and oblige me to listen, saying as she did so, "Do you realize your mother has chosen an extraordinary man as her husband? What gifts he possesses! How remarkable he is!"

“Madame," I replied one day, very seriously, "I will give him credit for all his other conquests, but I will never forgive him for having conquered mother."

The expression amused Madame Campan. She repeated it. It spread all over town. The reactionaries living around the Faubourg Saint Germain became enthusiastic over my attitude, attributing to me political opinions I never dreamed of having.

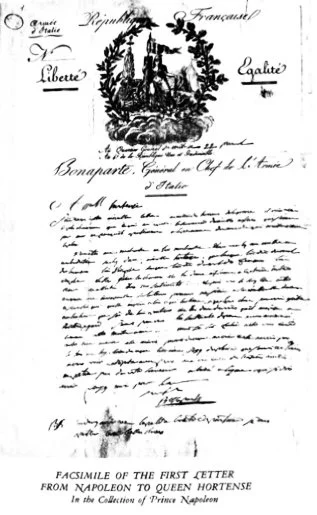

For some time, Madame Campan had been urging me to write to my stepfather. I had always refused. How could I be expected to express sentiments I did not feel? It was out of the question. Yet on the other hand I could not dwell on my disappointment that the marriage had taken place. I thought it best not to write at all, but as Madame Campan insisted, I finally yielded.

My letter centered around one idea and might be summed up as follows: "I have been told of your marriage with my mother. What surprises me is that you, whom I have so often heard speak badly of women, should have made up your mind to marry one of these creatures."

The General's reply was very long and written in an extremely difficult hand, practically indecipherable unless one were used to it. It was not till years later, during the Consulate, that Bourrienne, the First Consul's private secretary, revealed to me all the kind phrases it contained.

Napoleon’s first letter to Hortense.

It was about this time that I was confirmed. I took communion with all the fervor of a person whose soul is as ardent as it is innocent. My brother was confirmed the same day. Every Sunday he spent two hours with me in Madame Campan's private apartment. But I did not enjoy this pleasure very long as General Bonaparte sent for Eugene to go to Italy to act as his aide-de-camp. How cruelly I suffered at being deprived of the companionship of the brother I loved so dearly! The only consolation left me was the affection of my fellow pupils, the tender care of Madame Campan.

The latter worried about the intensity of my emotions. She sought to remedy what she called my excessive sensitiveness by developing my mind, by teaching me from the outset to beware of that impulsiveness which later in life might prove prejudicial to me.

Fortunately, I took my pleasures as seriously as I did my sorrows. As a rule I was very light-hearted, even hoydenish. This tendency to a great extent remedied my too keen "sensibility." I sought always to taste to the full every emotion, nothing was indifferent to me, everything affected me profoundly. At vacation time the mothers came to take away their daughters.

Wild and boisterous.

I remained behind. Apparently, I had no family of my own. I felt very sorry for myself. This was unjust, for no general, no aide-de-camp arrived in Paris from Italy bearing despatches or captured flags who did not also bring me messages and souvenirs from my mother. My stepfather also sent me watches and Venetian chains by his aides-de-camp Marmont and Lavalette.

Everything was done to show me I was not forgotten, that I was not really abandoned. My grandfather was living at Fontainebleau.

The Princess de Hohenzollern had left France a short time after the death of her brother the Prince de Salm. There was no one I could go out with. To be sure Madame Tallien asked me to spend a few days with her but I invariably declined. I did not feel that her circle formed proper surroundings for me.

My close friendship with Madame Campan's nieces helped me to bear the separation from my family, and occasionally I went to Grignon, their father's handsome estate.

One day, Madame Campan took us on an outing to visit one of her aunts who lived at Versailles. In the evening tea was served and other guests came in. Among them was a poet who became much interested in our party and particularly in me. I did not care especially for his attentions at the time but was overcome with surprise and even grief (I remember I cried like a child) when the next day I found in a newspaper some verses he had written for me.

Madame Campan laughed at the sight of my despair. "Just think, madame," I said sobbing, "he's only a flatterer trying to obtain my stepfather's favor. In doing so he is hurting me terribly. In order to be happy a woman must not attract attention, and here's my name in print in a newspaper. People will notice it, will talk about me, and I shall certainly be unhappy."

I began to weep again, perhaps with a foreboding of the future. Madame Campan realized I was too deeply upset for her to joke about the matter. She said to me tenderly, "Yes, people will talk about you. That is probably a part of your fate. Remember you must never do harm, for every act you perform will be known. The higher a person's rank, the more severely he is criticized. Accept what destiny holds in store for you. Doubtless it will be happiness, for you will be good and have reason to be satisfied with your conduct."

To return to my poet. My dislike for him was so intense that, fifteen years later, when he sent me one of his volumes with an extremely polite letter, the moment I recognized his name I threw away the book and the letter, exclaiming as I did so, "Ah, that horrid man. He brought me bad luck."

Madame de Campan tried to instill in the hearts of her pupils a feeling which very few women are conscious of, namely, a love for one's country. How many famous Frenchmen have been lacking in patriotism! Otherwise they would have spared France many of those misfortunes which resulted from their acts and which darken their fame. One should love one's country, and must be constantly ready to sacrifice oneself for it. This is what I sought to teach my children. Perhaps I succeeded only too well if fate keeps them forever from France, which I tried to make dear to their hearts.

Madame Campan also took great pains to form her pupils' character. She founded a good conduct prize, consisting of an artificial rose, to be worn on Sundays by the girl who received the most votes. Everyone, pupils, teachers, servants, cast a ballot. No one wished to compete against me for this prize and it was known in advance that I was to receive it. It was awarded me as expected.

This incident, the tears of joy it provoked, the enthusiasm it aroused produced on me one of the deepest and most agreeable sensations I ever experienced. Three months later another election was held. The discussions that went on about it set the boarding school humming. Among the four candidates for the rose was a young lady possessing many natural gifts, but inclined to be headstrong and willful; the hope of winning the prize had in a few weeks made her the most agreeable and obliging of us all.

Her rival, my cousin Emilie de Beauharnais, had to make no effort whatsoever in order to please. Her kind disposition endeared her to everyone but the question arose as to which was the more deserving of the two, she who can overcome her faults or she who simply follows the dictates of her nature. The question was debated with all that earnestness and passion which youth can command, and the day of the election might have proved a day of conflict had not Madame Campan, in order to satisfy both parties, divided the spray into two parts and named two prize winners instead of one.

On this important issue I remained neutral. It would have been too natural for me to vote for my cousin. While my schooldays passed thus quietly and calmly, the only incidents being such as I have just related, important events were taking place in the outside world.

The peace of Campo Formio had just been signed. Family affairs obliged my grandfather and his wife to stay in Paris. He wished to see me again. It had been a long while since I had been away from Saint Germain.

As I drove at nightfall across that square, where so many people had perished, the memory of my father, the thought of his tragic death rose before me. I wept silently, sitting in the back of the coach. I should have been ashamed to have others notice my emotion. Always I have attempted to keep my feelings to myself. I believe the deeper they are the more one restrains them. I had only been staying for a few days with my grandfather, when General Bonaparte arrived from Italy.

Paris rang with his name. Everyone sought to catch a glimpse of him in order to admire him. He lived at my mother's house in the rue Chantereine, which was promptly rechristened rue de la Victoire.

Emilie and Hortense

One morning my grandfather took us, my cousin and myself, to see him. What a change had come over our little home that formerly was so quiet. Now it was filled with generals and officers. The sentinels had difficulty in keeping back a crowd made up of all classes of people, impatient and eager to catch sight of the conqueror of Italy. Finally, in spite of the throng we managed to reach the General. He was having breakfast surrounded by a numerous staff. He greeted us as affectionately as a father might have done, gave me news of my brother whom he had sent to Zante, to Corfu, to Cephalonia and to Rome with the news of the signing of the peace treaty, and told me that mother would be home soon.

A few days later I did, as a matter of fact, have the pleasure of seeing her again and of going to live with her. She enjoyed telling me about her travels: how the troops of General Wurmser had fired on her carriage near Mantua how General Bonaparte when he heard of this had declared, "Wurmser will pay dearly for having frightened you"; and how shortly afterwards new victories had confirmed his threats. I remember also that in telling me about the honors she had received in Italy she spoke of a prophecy an old negress in Martinique had made before she was married about her future.

After announcing she would marry twice a long way from home and would have two children by her first husband, the fortuneteller had added, "Your second marriage will make you more than a queen. But beware of a priest who wishes you ill." My mother pointed out that the first part of the prophecy, which she had forgotten until now, had come true, as the successes of the French armies in Italy had made her more than a queen.

She never guessed these successes would carry her still higher. Nevertheless, the latter part of the prediction frightened her in spite of herself, and she admitted she was her nervous when she saw a priest too intimate with her husband.

Monsieur de Talleyrand, at that time Minister of Foreign Affairs, gave a great reception in honor of General Bonaparte. My mother took me with her to the party, and it was there I first saw Madame de Staël. She kept following the General about all the time, boring him to a point where he could not, and perhaps did not, sufficiently attempt to hide his annoyance.

It was at this ball that when she asked him, "Whom do you consider the greatest woman in the world, past or present?" Bonaparte answered with a smile, "The one who has had the most children."

Mother was naturally obliged to go out a great deal. I preferred not to accompany her and spent my evenings at my grandfather's house where I should be sure of seeing my cousin and the Mesdemoiselles Auguié.

Louis Bonaparte, who returned to Paris ahead of the General, also enjoyed our company. He came to see us often and seemed particularly interested in me. For some inexplicable reason I was afraid of him and took pleasure in convincing my cousin that it was on her account he called so often.

Louis Bonaparte

Emilie de Beauharnais Lavallette

Contempt for the laws, and the disturbance of public order, are the results of weakness and wavering in princes.